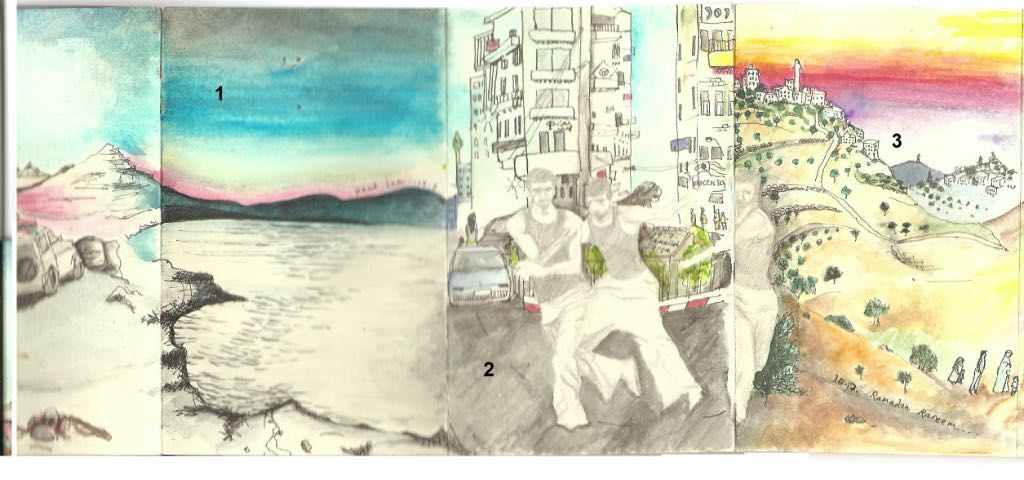

1. The Dead Sea

We float lazily in the thick and warm water, careful not to let our faces dip into the mineral concoction. The thick water restricts you from making sudden movements. You slowly learn patience, as you simply accept a lazy attitude. I had to learn patience while living in Palestine, and an attitude of ‘Inshallah’, roughly meaning ‘God willing’, and thus ‘we have no control over what will come’. As a foreigner you must learn to lie back – surrender – and take things as they come in order to participate with the lifestyle and culture of the people. Surprisingly, (between the numerous coffee, tea and humus breaks) things do get done.

The Palestinians within the West Bank cannot visit the sea, and they often told me as much. Perhaps because they are Mediterranean people who have lived close to the sea for millennia. Perhaps because it emphasizes how barricaded they are: within the walls of the occupation.

The Dead Sea, however, has parts open to both the Israeli and Palestinian public. I went there on four occasions. The first time was in Jordan. Jordanians (who are mostly Palestinians) must pay around sixteen dollars to swim in a tightly enclosed area of the sea. It’s restricted and closely monitored by the Israeli government in order to prevent people from crossing the border. And the people truly wish to cross the border. In Jordan, I befriended Palestinians who had lived in Jordan most of their lives. Although all of them were relieved to escape the suffocating atmosphere of Palestine, they missed their homeland. They wished to cross back to Palestine where they feel a connection to the land.

2. Dance in Ramallah

Ramallah is a very westernized city in the West Bank. Young women are more inclined to study rather than marry, and it’s easy to get swept up in the social life. Bars and cafes are crowded with active students and internationals. With Western luxuries, many can easily ignore the politics that pressure so many Palestinians in neighbouring villages or cities. One main concern for people here is the difficulty of getting permission to travel out of the West Bank, and then if they do, they’re left feeling more at a loss, as they realize how unjustified the conditions of their life are. I went with a few guys in their mid 20s to Jerusalem, and was surprised they wanted to visit the mall. While I sat bored, they were awe-struck by the traffic lights and clean streets. It was a massive culture shock for them, and they returned home frustrated with their lack of resources.

Ramallah is bursting with NGOs (Non-Government Organisations) and international volunteers learning about the Middle East (whilst living with their familiar luxuries). I offered to help out at a dance NGO in Ramallah. At this time, the streets of Ramallah were alight from day to night with miniature fires (which the police officers assured me were not a problem). Rallies of men would protest for economic reform, blocking the traffic in the city centre. Palestinian and Estonian volunteers ran the classes at the dance NGO. The classes promoted self-confidence and new forms of expression, which excited and inspired the students. Both the Estonians and Palestinians learnt English at school as a second language, which worked perfectly, as the Estonians spoke clearly and simply so the class could easily follow.

In the midst of economic downfall, many Palestinians within the NGO community were ignorant of the global economic crisis and had no clue that Estonia was undergoing a worse economic crisis than Palestine. The NGO I was working with was relying on volunteers to keep the organization afloat. It appeared to me that Palestinians in Ramallah have become accustomed to foreign aid and seem to expect it now. While they’re accustomed to it, feelings of helplessness increase and appear to be causing reliance. Effectively, many NGOs and charities patronise the people. It’s understandable, however, why foreign aid is sought. Their own government, the Palestinian Authority, is under Israeli domination, and cannot make decisions without Israel’s approval. Ultimately, West Bank residents feel politically powerless as well as geographically restricted.

3. Ramadan Kareem (Ramadan is generous)

Ramallah is a very westernized city in the West Bank. Young women are more inclined to study rather than marry, and it’s easy to get swept up in the social life. Bars and cafes are crowded with active students and internationals. With Western luxuries, many can easily ignore the politics that pressure so many Palestinians in neighbouring villages or cities. One main concern for people here is the difficulty of getting permission to travel out of the West Bank, and then if they do, they’re left feeling more at a loss, as they realize how unjustified the conditions of their life are. I went with a few guys in their mid 20s to Jerusalem, and was surprised they wanted to visit the mall. While I sat bored, they were awe-struck by the traffic lights and clean streets. It was a massive culture shock for them, and they returned home frustrated with their lack of resources.

Ramallah is bursting with NGOs (Non-Government Organisations) and international volunteers learning about the Middle East (whilst living with their familiar luxuries). I offered to help out at a dance NGO in Ramallah. At this time, the streets of Ramallah were alight from day to night with miniature fires (which the police officers assured me were not a problem). Rallies of men would protest for economic reform, blocking the traffic in the city centre. Palestinian and Estonian volunteers ran the classes at the dance NGO. The classes promoted self-confidence and new forms of expression, which excited and inspired the students. Both the Estonians and Palestinians learnt English at school as a second language, which worked perfectly, as the Estonians spoke clearly and simply so the class could easily follow.

In the midst of economic downfall, many Palestinians within the NGO community were ignorant of the global economic crisis and had no clue that Estonia was undergoing a worse economic crisis than Palestine. The NGO I was working with was relying on volunteers to keep the organization afloat. It appeared to me that Palestinians in Ramallah have become accustomed to foreign aid and seem to expect it now. While they’re accustomed to it, feelings of helplessness increase and appear to be causing reliance. Effectively, many NGOs and charities patronise the people. It’s understandable, however, why foreign aid is sought. Their own government, the Palestinian Authority, is under Israeli domination, and cannot make decisions without Israel’s approval. Ultimately, West Bank residents feel politically powerless as well as geographically restricted.

4. Al Axir Mosque

It is highly credited in Islamic culture to pray at the Al Axir mosque on a Friday. To break your fast there, too, doubles the credit points. One Friday, in the village of Zowiye, an elderly woman encouraged me to join sixty of the village women on their way to Al Axir mosque. They dressed me in a traditional dress and veil and – to my surprise – were happy for me as I, too, refused water and food throughout the day. One has to cross a checkpoint out of the West Bank to get to the mosque.

The road to Colundia checkpoint was a web of cars, all anxiously still in the traffic jam that stretched over six kilometers. The women on the bus were upright and stern as they stuck their heads out the bus windows, searching hopelessly for an end to the traffic. One of the older women calls everyone off the bus and onto the streets. We join the current of thousands. Winding through cars, we marched to the checkpoint. Each person was hungry and thirsty, and exhausted with the heat and yet as we marched through the car fumes there was no sense of pity. No one was heard complaining. And maybe it was the heat and lack of food, but I felt equal with everyone beside me. We shared a common struggle and that gave me strength.

We reached the checkpoint and queued for another few hours, watching person after person be turned down by two young Israeli soldiers who looked about my age. Even those with (paid for) Israeli permission forms were declined entry through the checkpoint. My friend and I, who held Australian passports, were the only ones accepted through, and we waved a pitiful goodbye to our friends on the other side of the glass.

5. My family in Nasara

My father’s family moved to Australia as refugees in 1962. Naturally, I desired to meet my relatives in Palestine and find the homes of my grandparents. It’s common for Palestinians to struggle with issues of identity, as their passports (their identity cards) restrict their movement and opportunities. However Palestinians outside of Gaza and the West Bank aren’t as restricted.

My relatives are stretched across “pre 1948 Palestine”, known today as Israel. Their passports allow them to travel under the condition that they, too, deny their heritage. Their passports call them ‘Arab Christian Israeli’. I mentioned the word ‘Palestine’ in a kebab shop one night. Silence descended upon the tables like a bomb. Slowly noises began to chime again casually, but later in the car I was severely warned; do not mention politics in public. The ironic thing was that I did not mention politics, merely the world Palestine. I asked my teenage cousins if they consider themselves Arab-Israeli or Palestinian. None denied that they feel more Palestinian though none would admit that in public. In public they are Arab Israelis.

It’s understandable that they struggle to identify their ancestral land with the name of Palestine. Palestine was completely different prior to Israel. Namely, there was harmony between the people of different religions; my grandparents had Jews, Christians and Muslims at their wedding in Nasara, Palestine. Today, just as the passports segregate people by their religion, the people, too, are separated. Christians, Muslims, Druze and even the people from each sect of Judaism tend to avoid one another.

6. Invisible walls

My brother met an Israeli named Esther in Australia and encouraged me to meet her. I mentioned this to a few Palestinians living within the West Bank, and a few in Nazareth. They all urged me to avoid her; she could be a spy. I decided that I could play the spy too and I met her anyway. All day long we toured Jerusalem, what she called the microcosm of Palestine and Israel. We toured different paths where Jewish Israelis walk. She said she had walked these streets for most of her life without ever seeing the Palestinian houses. In fact, it wasn’t until she travelled overseas until she learnt a more balanced history of the conflict.

We then wandered around the Palestinian suburbs in Jerusalem. Tourist sites were being built on destroyed Palestinian homes. We weaved between dirty streets, abandoned by government, and spotless city roads lit up by pretty lamps. Despite being only meters apart, the people from either side don’t interact. One pretty street we passed was where a local Palestinian was bashed to death by a local Israeli, just a week before. On the next, we see the hotel which was bombed around 6 years ago by a Palestinian suicide attempt.

At a bar in Jerusalem, I watched Esther convince eight random internationals to visit the West Bank. They were nervous, convinced that it would be unsafe, or hard to get in, or that Israel would catch them afterward and call them a spy. We visited the village Al Aqaba (wherein an Israeli military base exists) and stayed there for a night. The internationals were inspired by the kindness and hospitality of all the Palestinians we’d met en route. They made sentimental monologues about how the media is so wrong, and how they felt much safer in the West Bank than in parts of Israel. Like all villages in section C; the outskirts of the West Bank, Al Aqaba is forced to live in difficult conditions so that the people move inland; into the cities and thus diminishing the West Bank. It protests peacefully, however, having built the first ever mosque to hold a double pointed steeple, symbolising peace. It was, unfortunately, interpreted as the sign of victory.

7. Crossing the wall

Esther claimed that she could name all the other pro-Palestine Israelis (they are so few). Intrigued, I continued to meet Israelis and learn different views on Zionism. Being raised among Palestinians, I had envisioned Israelis to be intimidating, tough, and perhaps a bit inhumane. I was shocked to find them quite sensitive. They seemed to live in fear for their safety and wellbeing of their families and friends. A few told me that the whole world is against them, and that the Arabs will gang up against them. This fear gives the population, coming from varied countries with polar cultures and customs, a connection. Everyone my age and older – Esther included – could tell me a time when they or their friend had just escaped a terrorist attack, or how their cousin was hurt, or something, all to explain that they ‘have to protect themselves’. The Arabs want them dead.

The fear causes more men and women to stay in the army. All eighteen-year-old boys in Israel must join the army straight after high school; combat soldiers for four years, other boys for three years and the girls for two. At such a young age, they are strictly indoctrinated and traumatised as friends or fellow ‘brothers in arms’ are killed in combat. Although they have not spoken with them, Arabs are drawn as the enemy. Many Israelis told me that the Palestinians ‘deserved to be punished’, in various unjustifiable ways. Yet, when I mentioned that I worked in the West Bank, with autistic children, they considered it to be an admirable gesture; ‘Divine’.

8. Walls of Education

Prior to leaving Australia, I began to seek places where I could volunteer in Palestine. One Palestinian/Australian woman I know invited me to work and train with her in the West Bank’s first ever school for Autistic children. She, herself, was building it from scratch. Building such an organisation is arduous business, especially as you always need funding. We sought funding from big Palestinian businesses, who give generously over the course of Ramadan.

In Palestine, however, one must expect the unexpected challenges. Autism is fairly common, affecting over one child in every hundred, however it’s not understood; even among the professionals. The various schools specialising in handicapped children lack the facilities to provide for what the children need, and appear just like a regular classroom.

More importantly, the people were dumbfounded by the concept of Autism. One father had gone to every doctor through Palestine to Jordan, paying thousands, trying to find out what was ‘wrong’ with his child. He thought his son was sick and once, anxiously, asked me if I (of all people) knew how to cure autism. I was spending every day with Yusef so that he would become comfortable and responsive with a variety of different people. I could empathise with the father, it was infuriating to have this boy ignore me all day long, seemingly insensitive to my suffering. Perhaps through loneliness or boredom, I began to think like him and started to foresee his actions. It turned out that Yusef was very intelligent, and while he would not look you in the eyes, he would still notice what people wore, or if a usual item of their clothing was missing.

Yusef is not sick, I told the father, only different. He doesn’t need to be cured, only understood. The father didn’t understand. While the walls of the West Bank are closed off from the rest of the world, the people experience less variety of culture and philosophy, stinting education and one’s ability to learn new ideas. Mayada’s school, however, could only assist Yusef’s understanding of the world, rather than Palestine’s understanding of Yusef. Palestinians in the West Bank who are like Yusef (as well as their parents) continue to struggle due to the general ignorance of such mental disabilities, or differences.

9. The oil of your olives

Saeed is a Palestinian who has travelled the world, speaking at events about Palestine. I befriended him on Facebook after his talk in Australia, and he welcomed me to his village, Nil’in. While I stayed with him, he was organising his visas for a new trip. As a Palestinian, the visa application process is particularly difficult, even after he received the help of foreign countries. I had to take his application to Jerusalem for him because he wasn’t permitted to pass the checkpoint.

Nil’in is another village in section C (the outskirts of the West Bank), and after visiting for a few nights, I couldn’t resist returning for a few weeks to help out with the olive harvest. The residents were so fun and welcoming. Relaxing on the balcony of a friend’s house, we had a perfect view of the city. I could see the road dividing Nil’in, where Jeep cars (modern tanks) circle the two parts of the village constantly. Clearly, I could see the wall cutting through the olive fields and the Israeli settlements. Saeed pointed out his family’s olive grove; on a mountain beyond the wall. Most of the village lost their land after the construction of the wall. Nevertheless, it seemed that during the harvest the whole village were out on the fields. Although Saeed’s family aren’t allowed to visit their olive trees, neighbouring families allowed them some of their own. Like that, the whole village has a share of olives and its oil.

From five in the morning, we were out in the fields, singing songs of liberation as we brushed olives from their branches. We stood just meters from the wall, and as I scavenged the dirt for olives, my hands dug tear gas canisters out of the dirt. A nearby village had in fact turned the canisters into decorations; stringing them around houses like fairy lights. I would work with both the women and the men in turn. Some of the men were disconcerted, seeing me climbing the trees or ladders as they would. Surprisingly, the men had it easy. It was the women’s jobs that I found the hardest, as they would collect and sort every last olive, and separate it from the dirt (using the wind).

While I was there, I received news that a friend in Australia had died. Nil’in was a perfect place to grieve. I passed long days under the sun, picking olive after olive in a mindless cycle, contemplating the beauty of simple things in a village tormented.