“Full-time troublemakers”. This is how Chris Swinbank describes student activsts he camepaigned with during his time at the ANU from 1968-1971. After reading about Chris and the anti-apartheid campaign in a chapter of The Making of the Australian National University: 1946-1996 (2009) by Stephen Foster and Margaret Varghese, I found Chris on Facebook and met with him one afternoon in Cafe Garema, where he shared with me some of the history of ANU’s activist culture, stories of past campaigns and photo upon photo of rallies and arrests. Meeting with Chris was an important exercise—not only in preserving histories of radical action and dissent, but also in connecting faces with names and understanding what motivated the people who, like my comrades and I, spent their years at university as student activists.

Whilst many of these motivations are the same—socialist roots, a deep commitment to social and environmental justice, and an interest in and concern for human rights—speaking with Chris revealed to me the changing nature of students’ lives and how this has shaped the activism we engage in. Perhaps most starkly, our opening conversation about our backgrounds emphasised the barriers student activists now face fifty years on: not only on campus, but in our everyday lives as people living in an increasingly divided and unequal world.

As a graduate of Melbourne Grammar, one of Australia’s most elite private schools, Chris told me that he and the majority of the student activists he organised with during the late sixties and early seventies came from well-to-do backgrounds. Whilst holding little relevance to Chris, I couldn’t help contrast this to the activists I work with today, many of us publicly educated and coming from working class families. Throughout the great many stories and escapades Chris and I discussed, rarely had wealth acted as a limitation. This is a far cry from the conditions we organise under today, in which many activist groups struggle to retain core members who must spend their time in hospitality or call centres so they can afford to eat the next day.

This, I believe, is worthy of reflection when we write about student activism and consider the organising we participate in today. As inequality continues to grow under austere “budget-saving” measures, students are living below the poverty line on Youth Allowance, moving from one precarious share house to the next and struggling to find casual work (with penalty rate and workplace entitlements on the chance we do find employment). The increasing pressures that neoliberalism is exerting on both young people and social movements answers in part, then, the disparity between the grandeur and energy of the student activism Chris recounted, and the apathetic fragmented student population we now struggle to mobilise.

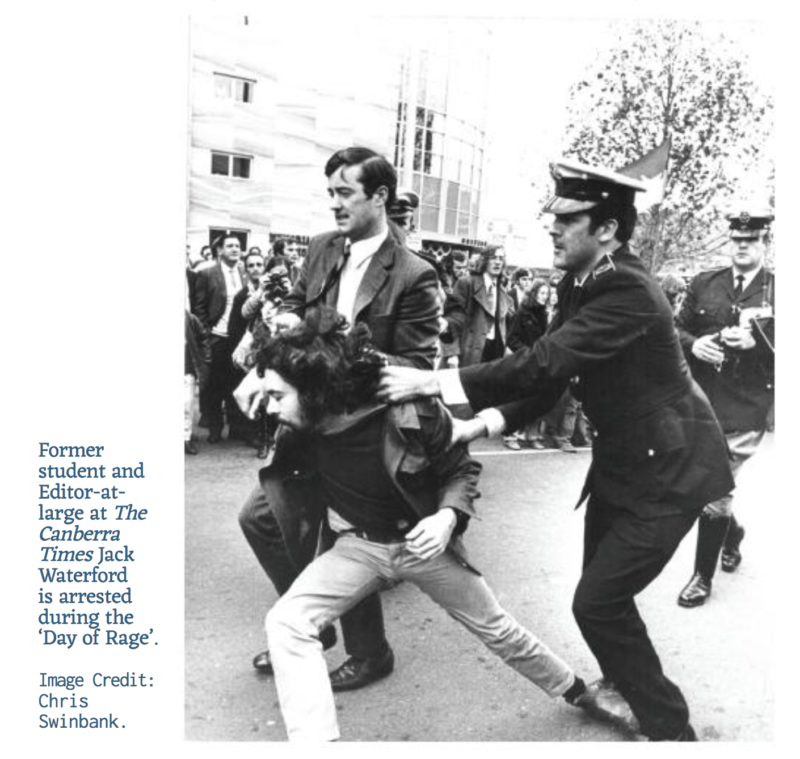

The picture Chris painted of activism during his years at the ANU was one of overwhelming enthusiasm and commitment; the kind of intoxicating student militancy we now yearn for. As he meditated on the thousands of students who had overtaken Civic on the “Day of Rage” against the Vietnam War, Chris nostalgically pointed over my shoulder, identifying the exact spot—only metres away from our cafe table—where Jack Waterford had been arrested during the demonstrations. Chris repeatedly emphasised the lack of apathy and big activist culture, mainly organised by word of mouth and Friday morning meetings at Tilley’s.

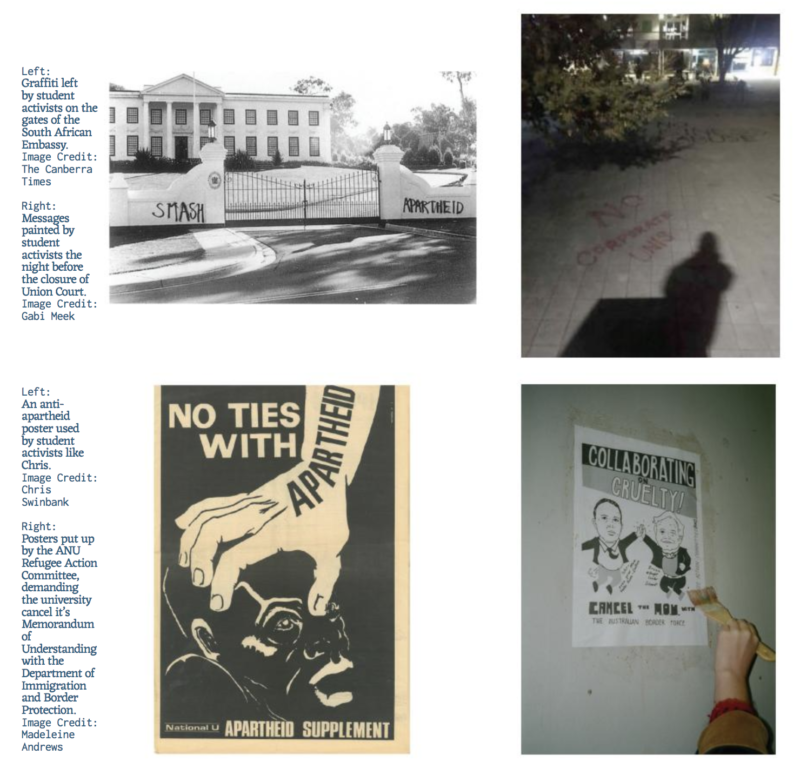

One particular example I found of this culture was in the scrapbook Chris lent us, filled with newspaper clippings and propaganda he had kept. Towards the back of the scrapbook was an old roster that had been drawn up by anti-apartheid activists, delegating names to specific windows of time during an astonishing six month, 24/7 vigil outside the South African Embassy. With almost fifty students prioritising the vigil over nearly every other aspect in their lives, the rigour anddedication achieved through one piece of paper was palpable. This is especially impressive considering the level of organising that was undertaken without social media and the technology student activists now rely upon.

Almost daily the student activists and groups I’m a part of, groups like the ANU Refugee Action Committee, use platforms like Facebook, Wickr and Wire to arrange stalls, advertise rallies and events, and coordinate more subversive activities such as occupations and the interruption of events. When I and three other student activists (Anna Dennis, John Dove and Con Karavias) crashed Education Minister Simon Birmingham’s National Press Club Address, we could not have effortlessly and secretively scoped out security, entered the venue and timed our disruption without instant messaging at our disposal.

This is not to say social media has revolutionised the way students engage in activism. In fact, organising online often lacks the same accountability physical organising produces. Nevertheless, Chrisand I both identified technology as a distinguishing factor separating our generations of student activists. Whereas we now use online petitions, or try and register as many tickets as possible to subvert formal events held by ministers like Peter Dutton, Chris and the student activists of the seventies would throw huge house parties, requiring attendees to physically fill out conscription forms with fake names and addresses to protest against the Vietnam War and clog the conscription process. Bearing in mind our different uses of technology and ways of communicating, I was interested to ask ho, if at all, students had connected across campuses to campaign together and converg as a united student movement. Perhaps we take for granted the value of Skyping into cross-country meetings, or the use of Facebook in organising simultaneous occupations as student refugee activists did this year. Regardless, Chris keenly labelled Canberra as the centre of protests, with Parliament House acting as a political hub and meeting place that brought students from across the country together; many travelling to Canberra for the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, for example. Likewise, big counter-cultural events of the seventies, such as the Aquarius Festival which was held in Canberra in 1971 and coincided with the “Day of Rage”, brought student activists together.

Despite all of these differences and generational gaps—the backgrounds we come from, the conditions we live under, the technology and tactics we use and the ways we communicate with each other—I found, after spending the afternoon with Chris, that the campaigns we dedicate ourselves to as student activists are remarkably similar. For Chris, his trouble-making years were largely spent rallying against South African Apartheid; dropping banners and postering campus with spray-paint cans in hand. Chris used the same sorts of tactics countless student activists use today, for example in the Refugee campaign. We talk to as many people as we can, disrupt public space and risk arrest in our attempts to raise awareness and rally against injustice. Northbourne Avenue has surely hosted us all, from “Toot Against Apartheid” on sunny afternoons in the seventies, to “Toot Against Offshore Processing” during dreary Canberra mornings throughout 2017.

Of course, divisions amongst activists were among the similarities Chris and I identified. During Chris’ time as a student activist, Trotskyists, Maoists, Anarchists, Labor Left students, as well as all other brands of revolutionaries competed with one another for media, recruitment and credit when organising. An inevitable fact of leftist activism, this division hasn’t changed. We do, however, work together more often than we don’t, and possess the same comradery Chris buoyantly reflected on when I asked about his fellow activists, commenting that many of the friends he organised with still share coffee and reminisce about what they used to do. Like Chris and his comrades, student activists today share a close-knit sense of community. Now, more than ever, we rely on each other for support: helping each other find work, a decent feed, and networks which allow us to survive not only at university, but also off-campus in the “real” world. Although we spend much of our time trying to transform the inequalities and injustices we see, we (like Chris in a different era) also spend our time transforming the little worlds we live in so that every day we can rise again to the struggles that lie ahead.