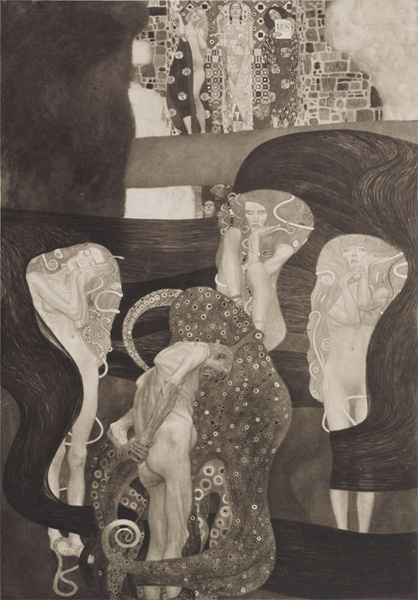

Jurisprudence by Gustav Klimt, source: Wikimedia Commons

The following notes respond to a prompt asking legal academics at ANU to write a short message to law students who chose to study law because they cared about justice. For such students, law school can be a disillusioning and alienating place. The intention of these pieces is to provide some assistance or consolation to students feeling this way, and to be a platform for honestly discussing some of the issues with legal education.

We hope these messages will be the beginning of an ongoing conversation. We are inviting responses from law students to these prompts. We would love to hear more about your experiences of law school and your reactions to these pieces. Did anything resonate with you? Did anything anger you? Were any of these assurances convincing, or is law itself inherently inadequate to meet societal injustice? What do you want legal academics to know about your experiences at law school?

Please email responses to demosjournal@gmail.com.

Dr Asmi Wood, Indigenous Peoples and the Law, International Law and Legal Education

Like many of our law students I too was once a young idealistic person who wanted to ‘make a difference.’ This aspiration was, however, framed in the inexperienced and groundless certainty of a young person, and it was probably a vague, non-specific hope, imagined in a fuzzy stream of consciousness that was bound to never ever be realised. However as we say in Torres Strait Islander law and lore, if the heart is right then the mind and body will surely follow. Consequently, now, as a not-so-young-lawyer, I remain, if not still idealistic, then perhaps still wanting to ‘make a difference for the better’ if not to the world at large, then more realistically to ‘my world’, whatever that might mean from day to day.

Historically this ‘world’ has been damaged by years of oppression, exploitation, neglect and discrimination. This extreme results in a world view that ‘never expects’ justice to be done, so is never disappointed, yet this also creates a debilitating inertia that does little or nothing positive to help ameliorate this situation. However, as with many indigenous people, I eventually realised that the causal link in this chain of intergenerational damage must individually be broken and this is a battle that can be taken head on and won. I chose the smaller battles, of trying to do what was better in the circumstances.

Yes, you are unlikely to make a difference to every child who is suffering but you can bring your legal skills and financial resources to make a difference to a single child or a battered person needing legal help. Even if we can’t help every asylum seeker or internally displaced person in the world, we can help a single asylum seeker to navigate the complexity of the law and language hurdles that they will face.

And for me? I know that I can’t help every Indigenous child gain the benefits of a Western education. But with the tremendous support of people like the law Deans at the ANU, our current VC and the remarkable strength and wisdom of people like Aunty Anne Martin of our Tjabal Centre and Professor Dodson of our NCIS, I can help young and not so young Indigenous people to avail the fabulous resources of our university and to realise that tertiary education is in many cases a very realistic and achievable goal.

If I were to articulate what I found useful as a yardstick in life, it is, that the sense of hopelessness is the true enemy of our species and that every positive deed, if thoughtfully and purposefully directed to the problems near at hand, can and most likely will, make a difference.

If shame is ever a motiving force, then one should feel ashamed, not because they could not complete the thousand mile journey but only that one never took that first crucial step. At this initial stage, it is crucial that you articulate what you consider ‘good and right’, and develop skills which you can then use to help you ‘improve your world’, and then set your heart firmly on using this knowledge and associated skills to do what is best for our broader community. Your mind and body will follow in time!

Justine Poon, Refugee Law and Legal Theory

Studying law can offer moments of great joy, in seeing an invisible system materialise through your developing understanding of it. In a system composed mainly of words, there is power in being able to articulate and advocate for how law should be. It can also be cause for despair when it seems that this all-encompassing system is at odds with your values and indifferent to questions of justice.

This tension creates an uncertainty that is necessary to do anything that is against the grain. The knowledge that you gain at law school plus uncertainty breeds hope: ‘This is the way things have been…but maybe it can be different’. ‘The law says x…but what are the reasons for that and is it just and should it be?’

Uncertainty is the impetus to explore the deeper structures of legal (and social and political) precedents and to search for the arguments that would be effective in making the changes that you want. It is also a way of staying somewhat distant and immune from the pressure to be doing or studying law in a particular way or working in particular places – you can take up those opportunities, but you can retain a healthy ambivalence instead of fully subscribing to the view that this is the one and only way to think about law and to do legal work.

To temper the discomfort of uncertainty, it is worth keeping a reflective journal in which you think about how what you are learning and doing reflects on your developing sense of values. This will help you keep track of the bigger picture and reorientate you in moments when you feel disconnected from your values.

Finally, good luck. It’s going to be a winding and weird road but you are going to do wonderful things. I recommend the book: Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit

Dr Anthony Hopkins, Criminal Law and Indigenous Peoples and the Law

Many of us come to law school because we have begun to see injustice, in our lives and in the lives of others, or even in our exploitative relationship with the earth. And we see that law is there, everywhere, entwined with these injustices, acting to validate or invalidate the distribution and exercise of power. With openness to possibility, we come to law school to learn about the law and to work with the law in the pursuit of justice. This motivation is clear and empowering, at least in the beginning.

Yet for many students, the experience of law school is one of learning rules – an often painstaking examination of legal categories, causes of action and elements. If we are honest about it, the idea of justice can get lost in a seeming reverence for the rules themselves. Knowledge of the law can come to define success for the law student, rather than the extent to which a student realises the justice to which the use of law, and law reform, can be put. This risks invalidating the core motivation that may have drawn a student to the law in the first place. Dissolution and alienation can follow.

What advice would I give, then, for the student of injustice?

Here it is easiest to reflect on my own experience. On arrival at law school, my concern was with the gross level of inequality existing in Australian society. I quickly found a focal point in the intersection between the criminal law and the experience of Indigenous Australians. It was with the failure of the criminal law to truly understand that the injustices of the past continue in the present, reinforced each day by our criminal justice system. This drew me to undertake a legal placement at the Aboriginal Legal Aid Service in Central Australia. There I found lawyers whose values I shared, whose motivation was the struggle against injustice and who used their knowledge of the law for their clients in this struggle. I met Aboriginal Field Officers whose generosity of spirit helped me come to understand the pride of their people, and the power of connection to country and kin. They taught me to work not just for people, but with them, as an equal, however different our lives might be. In this work, knowledge of the rules mattered. It mattered to those whose lives were caught up in those rules, and the intersection of life and law mattered as a foundation from which to call for change.

So, when dissolution threatens, as it will in law school – and in your work with the law as a graduate, wherever that may be – my advice is that you reflect on your deepest motivation and remain true to that. Continue to seek the revolution. But, also seek out opportunities to put your legal knowledge into action. The experience of working with and for people, or the planet, in the pursuit of justice is fundamentally empowering. Keep the justice question with you – keep asking it – and remind yourself that law is there and your knowledge of it matters.

Professor Desmond Manderson, Legal Theory, Law and Society and Literary Studies

A challenge that all law students face is the shift from other-directed to self-directed learning. This is generally true of university education but it poses a particularly sharp challenge for law students, who have been, by and large, unusually good at guessing what their teachers want from them, and giving it to them. Very often the approval that they get has become a vital part of their self-image.

You might want to read up on the myth of Narcissus and Echo—Echo who lost her voice and was condemned to repeat the words of others, Narcissus who fell in love with his own image and, blind to everything but his own beauty, wastes away to nothingness. The story contrasts two kinds of failed connection, two forms of emotional and intellectual etiolation. And it might be read as describing two aspects of the process of re-production in education, the way that it encourages sameness and mimesis, applauding the echo while affirming its own image. But of course, these anxieties of approval and recognition do not just go one way. You might want to ask – in the teacher student relationship, is it so obvious which is which?

Right up until university, we systematically discourage students from making their own judgments. But that is exactly what is needed if you want to really achieve something in your life – particularly when you are faced with a system that you think is unjust, unfair, or inadequate to the needs of the 21st century.

In a world like that, which is to say a world rather like ours, the narcissism of established interests, and the echo chambers of media and politics, might well be the real stumbling blocks to change.

This is not a plea to ignore criticism. It is the contrary. It is a plea to listen to it and never to be frightened of it. Above all, it is a matter of not taking it personally. It feels like the marks you get are the be all and end all of your education. They are not. They are merely the mirror in which is reflected the opinion of others. The more you actually worry about the marks you get, the less internal your motivation will be, and the less prepared you will be for a life in which meaning and motivation are up to you.

Of course, no one should doubt the extent of this challenge, particularly in an institution which is entirely structured around the pursuit of success in precisely, indeed almost exclusively, in these terms, and in which assessment is designed to steer you towards acting instrumentally and strategically about your education. There is a place for collective action to attempt to push the university and the college to seriously evaluate whether its approach in these areas is capable of making good on its self-proclaimed pedagogic and intellectual mission to produce leaders for the 21st century.

In the face of the kind of institutional and social structures that shape your education, it requires an enormous act of faith to wrench yourself free from the tyranny of narcissus and echo around you. But every small step of resistance to these norms is both an existential challenge and a liberating experience. It might free you up to do more, learn more, and to actually enjoy your time at this institution. For some students, law school is the pinnacle of their achievement. Don’t let that be you. Take a risk, learn lessons, and build within yourself the courage and the resilience you need to make a difference.

Moeen Cheema, Constitutional Law, Legal Theory and Law, Governance and Development

Legal practice has become increasingly globalised, cutting across geographic and jurisdictional borders in varied ways. Yet, legal education, particularly in the black letter mould, remains largely confined to jurisdictional boundaries. In addition to a handful of survey courses on law in other jurisdictions, law schools often seek to plug this glaring gap in legal education by providing rare and highly coveted opportunities for international exchanges, internships for credit and work placements.

Such opportunities to experience firsthand the workings of another legal system and immerse oneself in a different legal culture remain a limited part of legal education. Therefore, it is imperative that when such opportunities arise law students should seek to make the most of them.

One important way in which law students can frame such engagements with another legal system and culture is to explicitly and consciously encounter the tension between the universal – claims of rights, rule of law and democracy – and the relative and deeply contextualised foundations, structures and norms of the ‘other’ legal system.

This would require on the one hand avoiding the pitfalls of legal ethnocentrism and seeing these other legal systems in comparison to ours as primitive, dysfunctional and further down a universal development trajectory. On the other hand one must also avoid a kind of legal voluntourism – that is, seeing these other places, people and legal systems as exotic, unique and mysterious. There is a lot to be gained from taking the other legal system as you find it and on its own terms, while simultaneously questioning its popular myths and self-justifications. In the process one may learn to interrogate the history, foundational myths and self-rationalisations of our legal system – and its assumptions of rights, rule of law and democracy.

Professor Stephen Bottomley, Corporate Law

My reason for choosing to study law was a sense that knowing about the law would give me a good basis from which to understand the forces that shape the world, and to do something with that knowledge.

At the time, I had no clear idea about what I wanted to do when I graduated, and I certainly never contemplated being Dean of a law school. But whatever it was, I hoped it would be something to do with using the law to address over-reaches of authority and unaccountable exercises of power.

As a student, I studied company law, and I did not like it. Company law, and the corporate world, was the antithesis of why I had chosen to study law. And yet today I’m a corporate law academic. What happened? I hope that the following short explanation might help others as they grapple with similar questions.

It would be fair to say that in most discussions about social justice, corporations and corporate law are usually cast as the cause of social justice problems, rather than solutions. And certainly, there is a lot that the corporate world has to answer for. But I don’t think that any serious progress can be made with a social justice agenda unless it includes serious engagement with, and understanding of, the corporate sector.

This is not simply a case of ‘knowing the enemy’. It is an over-simplification to paint all corporations as ‘the enemy’. Instead, it comes from thinking about the ‘social’ in ‘social justice’. Corporations are one of the most significant actors in society. I have come to understand that corporate law is not just a branch of business law; instead, it is the law governing a major form of social organisation. Corporate lawyers need to understand this, and so do non-corporate lawyers.

Amongst other things, a concern for justice is a concern with ensuring the responsible exercise of power in society. By ‘responsible’ I mean being open, answerable and non-capricious. The exercise of corporate power must respond to these criteria. The world needs corporate lawyers who are informed about social justice issues. Corporate lawyers can, I hope, ensure that corporations – and their directors and shareholders – exercise their power responsibility. We need social justice lawyers and activists who are informed about corporations and corporate law, and who understand what can legitimately or practicably be asked of corporations. This is one of my key motivations for teaching and researching corporate law.

Professor Simon Rice, Anti-discrimination Law, Human Rights Law and Law Reform

I didn’t enjoy my first year of law school very much. I really didn’t know why I was there, except that people said I’d be good at it, it was what a lot of people were doing, and my mother was a lawyer.

A conversation with my parents wasn’t as hard as I had feared. I deferred for a year, and worked and travelled. I missed being a part of what my friends were doing, but I made different friends, at work and on the road. I grew up a lot.

After a year I went back to law school, with not much enthusiasm. At least I felt more relaxed about myself. At the beginning of third year I volunteered at a local community legal centre, and that was what did it: I had stumbled on something that gave my legal studies meaning. So, for the rest of my degree, I worked at the legal centre, directed and acted in law revues, enjoyed my share house, and got through exams and essays. The courses that made a real impression on me were the clinical course and an elective on welfare law, because they were taught in a way that respected me as a thoughtful, adult learner, and allowed me to explore the place of my values in law.

Once I graduated I travelled again, for a year and a half. It was over eight years since high school by the time I started work as a lawyer. I worked in a commercial law firm and then a community legal centre, and then went travelling again, for another year and a half. Eventually I settled into work in community legal centres, legal policy and human rights. These experiences were a pretty good basis for becoming an academic, where I can reflect on, research and teach many of the questions that the rush of legal practice leaves unexplored.

Along that journey I took some financial, professional and personal gambles, but I was conscious that my education, health and family, and my being a cis white hetero male, gave me security that I know others do not enjoy. Perhaps the hardest thing was to do what I wanted and felt was right, rather than what was expected and conventional.

I attribute little of what I have done and what I know to what I learnt in exams and essays at law school, and much more to reflective experience. I did learn rational, legal reasoning, which I have since tried not to unlearn but to be conscious of and careful with. I also learnt, and I still carry, a sense of a lawyer’s obligation to pursue justice, and of the power and privilege that lawyers enjoy.

One of the most important things I now know in my professional life is the antithesis of what I was taught at law school: that ideas of justice, fairness and what is right and wrong are complex and contested, and much more so than our conventional ideas of law can manage. To be understood, at any one time and in a particular context, they require thought, reflection, insight and humility. In teaching, research, writing, advocacy, and the legal practice I still maintain, that’s what I work on every day.

Michelle Worthington, Corporate Law and Legal Theory

One of the most remarkable things about law school is that we rarely talk about values. It’s easy enough to explain: the predominance of legal positivism and the ‘no necessary connection’ palaver; the adversarial system; even the simple fact of time pressure created by the semesterisation of subjects and the commercialisation of universities. But the fact that we can explain the absence of any serious, prolonged discussion of values in legal education does not make it any less notable.

After all, law is values. Simple as that.

Despite this fact, it Is possible to go months – years even – without ever having to think about law in these terms.

Who knows exactly what the effect of this omission is over time? My own experience is that it can make the law feel distant from our concepts of justice.

Sure, law and justice might not align, but they should never appear as separate.

To those students who chose to study law because you were interested in justice – your intuition was correct. Law and justice are inevitably, inalienably connected. The basis of this connection is values.

‘Law’ is a system of values, or rather, rules set up to cement certain configurations of values in certain situations. Likewise, ‘justice’ is a term which can be used to describe our comfort with particular configurations of values, especially those where ‘fairness’ or ‘equality’ are high in the mix.

This is why we can have sensible conversations about whether a law is just or unjust. And more importantly, about why a law is just or unjust. In fact, given our democratic aspirations, the interplay between law and justice could conceivably be the true lawyerly preoccupation: ‘Yes, but is it just?’.

My advice to students? Make your values, and those of the law, your focus.

Professor Tony Foley, Criminal Law, Legal Education and Indigenous Peoples and the Law

Before your law degree is over, I would recommend trying to get yourself some exposure to law in practice in a public interest setting. This can be in a clinic, in a Law Reform & Social Justice group, in an internship, or through volunteering.

The secret about this is not to focus on getting yourself skilled up with the thought of practice (that can come later in your GDLP). Instead the important thing is to find time and space to reflect on what you see – Does law produce justice? Does law really work to affect human behaviour? Does law work to protect the rights of vulnerable people? Is the peculiar role of a lawyer one I am going to be happy in? This article ‘Why would anyone want to be a public interest lawyer’ has come my way recently from one of our clinic teachers, it may get you thinking.