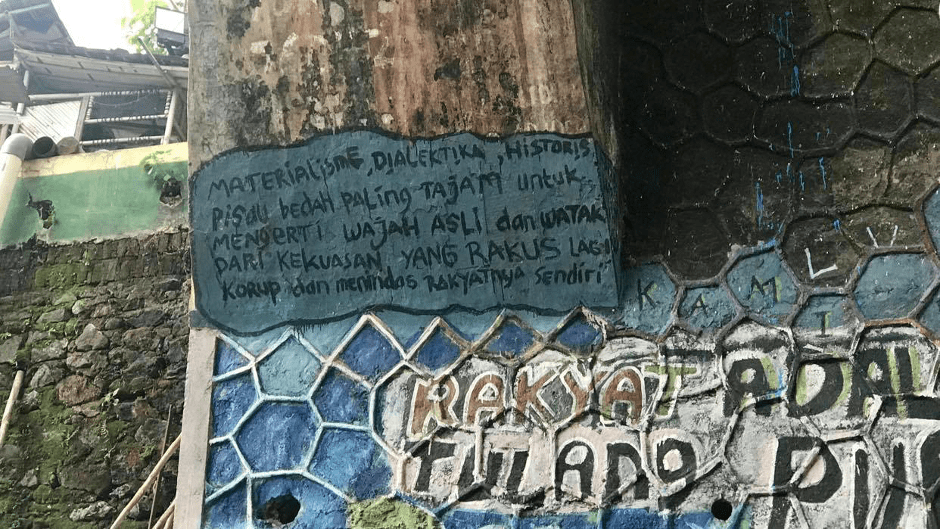

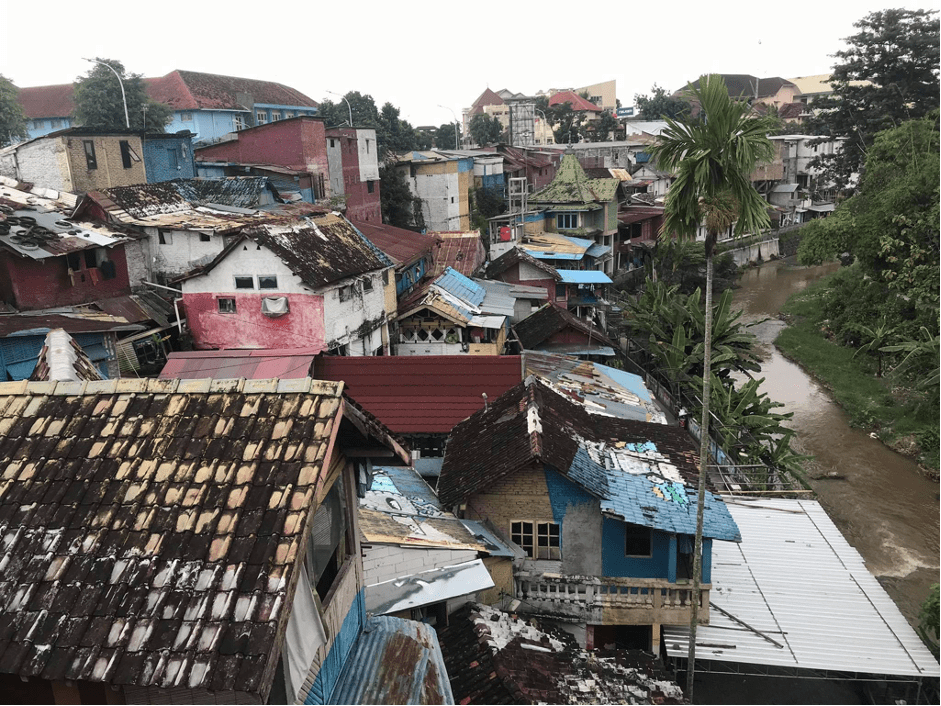

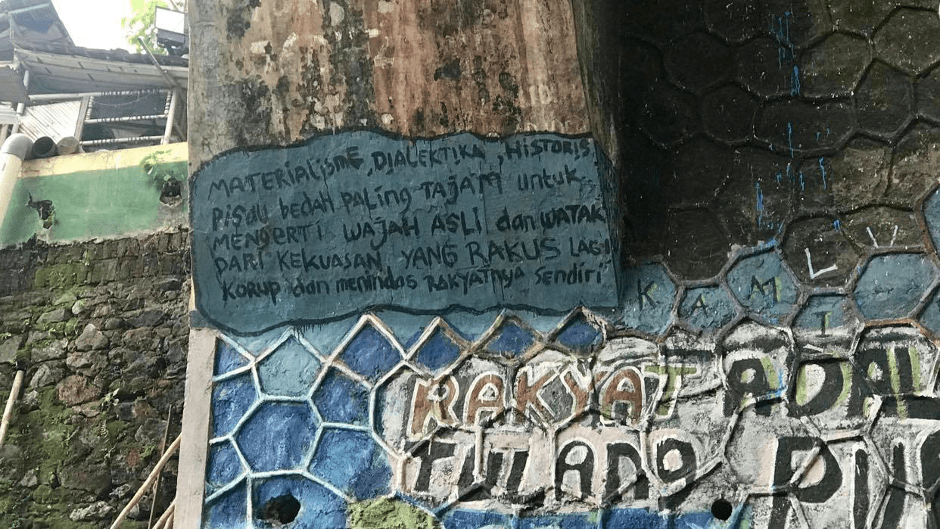

If you are to follow the path of River Code in Yogyakarta and then navigate your way under the Gondolayu Bridge you will come to Kampung Code, a riverbank settlement in Yogyakarta made up of brightly painted houses and murals. This settlement has had a turbulent history. In 1983, the then squatter settlement had been earmarked for eviction and it was through the intervention of Romo Mangun[1], a late priest and architect, that the settlement was saved. Supported by student activists Romo Mangun went on hunger strike to protest the removal of the settlement and used subsequent media coverage to showcase the lives of those living in the settlement (Guinness 2009, p.219). In 1992, he was awarded the Aga Khan award for his upgrading project and design work in kampung Code improving many of the homes. The status of this settlement is now somewhat secure, and the bright houses have been felt as a colourful addition to the city for a while now. However, the threat of evictions has not disappeared from Java. Although there was an attempt by the Sultan of Yogyakarta to reclaim all riverbank land in 2015 (Guinness 2020, p.428). In the same year Jakarta saw violent clashes between the police and residents of ‘illegally’ built homes along the Ciliwung River.

My PhD research, postponed due to Covid-19, was aimed at trying to understand how those living in places like Kampung Code have found ways of navigating precarity and engaging with the state from the margins, as well as investigating how this has changed since Indonesia’s transition to an electoral democracy and its embarking on a massive decentralisation program. Although Indonesia has undergone a dramatic transformation since the famous intervention to save Kampung Code, questions of evictions and interaction with the state have not disappeared for those living in poor urban Java.

Precarity has become identified as a motivator in large scale social and political shifts, not only by social scientists but also by popular commentators. Consider how common it is to see or hear arguments that populist movements such as Brexit or the election of Trump has roots in a working-class population who consider themselves left behind by an uncaring elite. These analyses often suggest that precarity is an imposed situation on populations abandoned by the state. The consequence of this is the reading of precarity as funnelling political responses towards populists. Guy Standing’s The Precariat (2016) for example, argues that precarity has led to the sharpening of divisions within society often manifesting in the villainisation of migrants. Many analyses of precarity in the global north have an understanding that the state has withdrawn from its regulatory capacity to allow for the market to restructure employment relations, these authors also typically theorise state activity and processes in a declining involvement in the provision of social services.

In the global south, analysis of precarity takes on a markedly different analytical framework often focusing on those working in the informal sector or living in large informal settlements. In Indonesia precarity has been cited as motivation for a variety of political and social phenomena. Economic precarity for the middle classes during the Asian financial crisis in 1998, and Suharto’s response to it, is routinely identified as a key reason, or accelerator, for the collapse of authoritarianism. However, it is also cited as a motivator for anti-democratic behaviour. Democracy in Indonesia (Power and Warburton 2020) identifies the re-emergence of populism in Indonesia’s electoral politics running along a well-established pluralist-Islamist division. Mudhoffir (2020) argues that the combination of economic precarity and the absence of a class-based politics in Indonesia has helped funnel discontented lower middle-class Indonesians towards populist Islamist movements, such as Aksi Bela Islam (defending Islam action) the protest movement that called for the then governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (more commonly known as Ahok) to be punished for alleged blasphemy.

I am interested in understanding precarity differently, namely from the point of view of those who navigate precarity from a position of being subject to long-term structural violence. Precarity is a situation that groups, and individuals find ways of negotiating. It is neither something to be celebrated nor totalising in its oppressiveness. Precariousness in my use of the word here can be thought of as being characterised by uncertainty and insecurity in multiple ways for those in Indonesia’s kampung, not only with regards to employment but also evictions and floods. My use of precarity is not defined by middle-class anxieties around declining incomes but instead focuses on groups whose histories have always featured some form of precarity. Rather than identifying it as a causal factor for populism or a consequence of the retreating role of the state in the economy, I am interested in how existing structures are repurposed and used by those who live in precarious situations. Taking Butler’s account as definitional support for my understanding outlined above, I analyse how poor urban spaces, often referred to as kampung in Java, have long been sites of precarity despite the ongoing presence of the state.

[1] Romo Mangun means Father Mangun, Yusuf Bilyarta Mangunwijaya was his full name.

Kampung is a word that evades easy translation into English, and within the Malay-speaking world it has multiple meanings. The word initially was associated with the compounds of wealthy families. In Malaysia, Brunei, and non-Javanese Indonesia kampung is most commonly used to describe a village and in Malaysia and Brunei the term also refers to local government administrative units. In Indonesia phrases such as pulang kampung (to return to one’s hometown) are often used especially during holidays such as mudik. Kampung can also refer to areas inhabited by specific ethnic groups. For example, an area with a high Madurese population might be referred to as kampung Madura. Or as my host family in Yogyakarta, for example, jokingly referred to an area we had lunch in one day as kampung boleh (area for white people) due to the popularity of the area with Europeans and Australians.

Another definitional twist to the term kampung can be found in the use of the term in Yogyakarta during the early period of the city’s court history. The initial kampung in Yogyakarta were the residences for the sultan’s workers (Soemardjan 1962). For those living in Java’s cities kampung has another distinct meaning; that is poor urban communities. It is in the final sense of the word that I am using kampung. Those living in kampung often have strong ties with their communities. The urban kampung of Java I am discussing here are sites of very real precarity insofar as people often survive through informal work and fear evictions. Floods, likewise, pose a very real threat for those communities built on the sides of rivers, especially during the rainy season.

While not all kampung are poor and the term stretches in different and interesting ways, those precarious, slum-like areas are often referred to as kampung, which is why I have chosen to use the word here. It is through a shared commitment to community that those in kampung often find ways of navigating with the state. Sullivan’s (1992) emphasis on the sense of home community and local citizenship is important to keep in mind here as this is key in enabling those living in these areas to negotiate with the state, using community structures that are in part state imposed.

In contemporary Indonesia, many kampung have been transformed into typical neighbourhoods with paved roads, access to formal land tenure, healthcare, and schooling. As such many of the tight-knit communities in kampung that were characterised by their exclusion from Indonesia’s large urban centres have become upwardly mobile spaces with access to formal jobs. Much of this has been due to the successful navigation of precarity and use of urban development programs to their own advantage, as well as ongoing economic growth over the last two decades.

However, the histories and geographies of most kampung fly in the face of the types of urbanism that we associate with strong state intervention in cities. States have often tried to govern their populations through a range of techniques that make the populations they govern legible (Scott 1998). In order to make cities legible there is the need to organise, map and turn it in an administrable object. Precarious people are inimical to this process, which leads to gaps in the way the state administers the kampung. Kampung have an internal social logic that guides how they order social life. Unable to fully control this, the state has found ways of enmeshing itself into these seemingly unplanned areas. Scott’s work on legibility is helpful to keep in mind when we think about how navigating precarity and negotiating with the state in Indonesia for two reasons. Firstly, the history of kampung in Java have continually disrupted the visions of those who would try to order and “beautify” the city and secondly, making urban populations legible is a key element of the urban government system that extends into kampung giving both the opportunities for negotiation with the state and also the folding off populations into the state’s bureaucratic rendering of communities.

The existing urban government system allows for the extension of the state into kampung as well as providing a basis for those in kampung to organise their communities. During intense periods of urbanisation in Indonesia (of which there are multiple historical examples) the housing supply has often been too low to accommodate the new rural to urban migrants who have often constructed informal settlements as accommodation. Urbanisation in Indonesia is a complex historical process with multiple causes that cannot be fully elucidated here. However, it should be noted that various regimes within Indonesia’s political history have watched the growth of these urban spaces and had to alter and rectify their governance structures in order to properly govern the cities. This was especially so during the Japanese occupation period (1942-1945) as the war time occupying power reorganised a number of the Dutch forms of government to facilitate the extraction of labour and to conscript Indonesians for the war effort. During this period the model of neighbourhood governments were imported to Indonesia (Reid 2011, 24). The organising of neighbourhoods into administrative units with unpaid elected heads facilitated interaction between the state and kampung communities (Kurasawa 2009).

The explosive growth of slums in the last decades, especially in the Third World megalopolises from Mexico City and other Latin American capitals through Africa (Lagos, Chad) to India, China, Philippines and Indonesia, is perhaps the crucial geopolitical event of our times. – Slavoj Žižek, 2008

Looking down at Jakarta from the sky, beyond the huge highways that crosscut the city, and the large public monuments such as Monas, you could point out large areas that show no evidence of the organising and discipling vision of modernity that the Dutch colonisers, and subsequent Indonesian governments have attempted to stamp on its urban form. While much of Java’s urban environment has developed without the explicit consent of the state and does not met the aesthetic vision imagined by urban planners, it is not hard to see either the state or precarity within Java’s cities.

Analyses of precarity are useful in shining a light on the ways in which seemingly totalising structures such as states or economic systems reduce human potential, embed inequality, or tolerate poverty. While these analyses are undeniably key to understanding structures of oppression and the axes they operate on, it is equally important to pay attention to how those living in insecure situations exercise their own sense of agency. Theoretical or large-scale analyses of slums often identify them as spaces the state has retreated from, and where the state’s presence is acknowledged it is often only in the form of coercive power. Slavoj Žižek (2008) and Mike Davis (2005) are two theorists who have discussed slums, urban precarity and their relationship with the global economic order. For Žižek slums can be thought of as one of the few international “evental sites” for our current political situation. Davis sees a planet of slums emerging as a consequence of the ‘urban explosion’ across the third world’s megacities and producing sprawling shanty towns in peri-urban areas.

Žižek and Davis are partially right in understanding the state’s relationship with slums as one of withdrawal and abject neglect. Žižek writes

Although they are de facto included in a state by the links of black economy, organized crime, religious groups, etc., state control is nonetheless suspended therein; they are domains outside the rule of law. (Žižek 2008, 42).

Like Žižek, Davis also emphasises the growth of a population outside of the state’s control and view. Kampung reveals ways in which people who live in slums do engage with the state and illustrates how the Indonesian state has not withdrawn entirely. Barker (2009) in his critique of how Žižek and Davis theorise slums has argued that the state has not withdrawn from kampung in Indonesia. Instead Barker proposes that the state has actively aimed to “intervene in, administer and control slum life” (ibid, 49).

Barker, by focusing on how the state exercises an unofficial form of coercion in kampung, corrects and adds to the ‘planet of slums’ hypothesis put forward by Davis. In addition, during the New Order period (the authoritarian era of Suharto’s presidency between 1966-1998), the state made and remade itself through a range of development-focused programs as a number of studies show (Sullivan, N 1994; Murray 1991). Anthropologists were able to provide a useful understanding of how development focused programs aimed to embed the state and forms of control into the kampung. The prevailing consensus amongst those who have studied kampung is that the ‘planet of slums’ hypothesis does not fit the Indonesian case, in fact Newberry describes kampung as ‘stated communities’ writing

In many ways, kampung are a kind of “stated” community, and I use that term to suggest two things. First, the image of the ideal community has been significantly tied up with state rule, whether it be the pre-colonial, colonial, occupying, post-independence, or modernizing state. In all cases, state rule seems to have required both the real community, as a form of social organization and administrative unit, and the imagined community, as a way to mobilise the populace. Second, these communities are stated as a rhetorical map of a nostalgic past and a modern future. The first meaning refers to the state-driven organization of local communities, and the second to the ideal community being pronounced by the state. Yet, whatever the original character and intent of the formation of this ideal type of community, it is the connection to kampung sentiment and its local use that gives it meaning in the life of local residents. (Newberry 2006, 41)

What Newberry, and other anthropologists (Guinness 1986; 2009; Sullivan 1992) have shown is that part of the reason the Indonesian state has been able to effectively keep a form of government in kampung is due to the entanglement of community with the state (see also Herriman 2012), especially through the neighbourhood government structures. Instead of focusing on the various ways states have exercised their control in kampung, I will instead focus on the other side of this equation. I want to suggest that those who live in kampung regularly ‘seek the state’ to borrow a term from Herriman and Winarnit (2016). A theory of seeking the state suggests how those in kampung actively use state structures to their own advantage. Paying attention to the way those in kampung seek the state also brings us closer to addressing another critique of the ‘planet of slums’ hypothesis, which is that in Davis’ descriptions of urban poverty he does not see any “people or social forces capable of challenging the social order” (Angotti 2006, 961).

Kampung residents navigate precarity by tactically engaging with the state when it is suitable and often masterfully using Indonesia’s complex system of government to their own advantage. Although this is far from the only way they navigate precarity. Lont (2005) has detailed how arisan and simpan pinjam (forms of financial self-help and loan) groups have found ways of providing community support for those who have become ill, had a family member pass away or lost income from unemployment. We could understand this as another tactic of navigating precarity. In the same way that the state is sought by those in kampung here there is a mobilising of community and drawing on a sense of shared belonging with immediate neighbours, if not a larger neighbourhood.

These claims are made possible through the cultivation and use of links with formal political representatives and institutions, often involving exchanging votes for the provision of goods or services. Guinness (2009, 64-5) has written how in Yogyakarta the election of the neighbourhood head is a reflection of a shared understanding among residents of the kampung of how some members of the community are better able to navigate the state structures than others. These types of understanding are also reflective of a community that knows and understands one another’s skills and capacities. This is another example of how the state and community and have found ways to tesselate with one another. Along with understanding the bureaucracy and other levels of government, those elected as neighbourhood heads are also expected to make links with urban elites who have typically dominated high political positions.

The urban poor in Indonesia have effectively found ways to exploit the weakness of Indonesian party politics through political contracts (kontrak politik). These can be understood as agreements created with electoral candidates for the provision of goods in exchange for votes. These agreements are often characterised by mistrust between the two parties and contracts are sought to try to instil a sense of accountability to those candidates who sign them. These links between the urban poor and political candidates are often mediated through NGOs such as the Urban Poor Consortium. The NGOs will typically work with a trusted member of the community to develop a link with the community or draw on the existing neighbourhood heads to galvanise the community into voting one way or make particular demands of candidates. Those who broker agreements or gain office can often betray their new constituents or find themselves unable to deliver on the types of promises they made (Aspinall 2014). Post-authoritarian political parties in Indonesia are typically weak with little grass roots support. Political scientists have long been pointing out the rise in candidate-based campaigns and parties’ inability to maintain strong support among voter bases.

One such example of kontrak politik is that signed by the current President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and a group of organisations representing the urban poor in Jakarta during the 2012 gubernatorial election (Hutchinson & Wilson 2020, 278). Within the contract with Jokowi, the kampung dwellers formulated a number of demands including the right to tenure, a halt of evictions, and acknowledgement of the street economy, which is often informal (ibid 278-9). Gibbings et al. (2017) have shown how these political contracts have been important in securing the rights of street vendors to earn a living without harassment from the state. The role of street vendors was important to Jokowi during his time as mayor of Solo where he would actively negotiate the movement of street-vendors for the formalising of their work.

The use of kontrak politik in this instance was only marginally successful as Jokowi did relocate some communities away from flood prone areas and begin a slum upgrading pilot, however, the promise to provide legal tenure for those unrecognised kampung was abandoned and evictions continued often without the provision of adequate housing to replace those removed from the kampung (Hutchinson & Wilson 2020, 279). Furthermore, Jokowi’s successor in the role of governor of Jakarta, Ahok, increased both the volume and rate of evictions (Tilley, Elias, & Rethel 2019).

Negotiation of this style with the state is an imperfect tactic that mitigates the insecurity of kampung life. The cultivation of links with members of the urban elite or the use of ‘adversarial linkages’ points to a creative use of government structures for the purpose of non-elites in an elite dominated setting. However, these negotiations are also ways of elites and the state achieving their ends. The realities of precarity do limit one’s agency and these negotiations usually result in the state making kampung populations legible in a way that is beneficial to the state. Chatterjee (2011) has argued that in many former colonies, political power operates through the productive interaction of non-state local communities and formal state channels. Herriman (2012) has also written how this operates in rural Indonesia with regards to the policing of local populations. People in the kampung have developed a method of seeking the state and making themselves legible in order to gain security.

This type of tactic for providing a sense of security and making material gains is often the only effective channel available to register political complaints or wants. The use of kontrak politik can be read as a failure in the political parties of Indonesia to properly develop grass roots support, however, it can also be read as those living in kampung manipulating cracks in national and local politics to their own advantage.

Precarity is an ever-present reality for those in Java’s kampung. Evictions, floods, and financial hardship often crowd the horizon for Indonesia’s urban poor. Often, all of this occurs with an ambivalent state deeply embedded in the daily life and social reproduction of the inhabitants. Kampung communities and the state have become co-constituting concepts. The current system of urban governance and kontrak politik in place in Indonesia is unlikely to uproot in the near future. This is largely because the structure has served multiple political orders in Indonesia as well as affording those within kampung opportunities to organise their communities and provide an avenue to make claims on the state, albeit a very narrow one.

Identifying precarity in kampung, and areas or urban poverty more broadly, should, however, be a starting point not a conclusion. The strength of Davis and Žižek’s large scale and theoretical arguments is the understanding of the creative and political potential that can arise from these sites. I agree with their understanding that precarity and poverty are not an aberration of the global economic order but are an integral part of it.

What anthropologists and other social scientists working with those who live in kampung have been so useful in showing is how those who live in kampung navigate their precarious reality, often through reworking political institutions for their own ends. I hope to have done some justice to the aspirations and creativity of people in those communities I was meant to work with. The navigation of precarity is often facilitated via a community with shared interests and connections but a community that is also entangled and mapped in the state’s processes and ordering of the world.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Patrick Guinness at the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University who read an earlier version of this article and provided helpful feedback. Also, thanks to Clara Siagian for help with a translation issue and for the various conversations that have helped me better understand this topic.

Angotti, T, 2006, ‘Apocalyptic anti-urbanism: Mike Davis and his planet of slums’, International journal of urban and regional research, vo.30, no.4, pp.961–967.

Aspinall, E 2013. A nation in fragments: Patronage and neoliberalism in contemporary Indonesia. Critical Asian Studies, vol.45, no.1, pp.27-54.

Aspinall, E 2014, ‘When brokers betray: Clientelism, social networks, and electoral politics in Indonesia’, Critical Asian Studies, vol.46, no.4, pp.545-570.

Azis, A, Ariefiansyah, R & Utami, N S 2020, ‘Precarity, Migration and Brokerage in Indonesia: Insights from Ethnographic Research in Indramayu’, in The Migration Industry in Asia, ed. M Bass, Palgrave Pivot, Singapore, pp.11-31.

Barker, J 2009, ‘Negara Beling: Street-level authority in an Indonesian slum’, in State of authority: The state in society in Indonesia, eds J Barker & G Van Klinken, pp.47-72.

Berenschot, W, & van Klinken, G A 2018, ‘Informality and citizenship: The everyday state in Indonesia’, Citizenship Studies, vol.22, no.2, pp.95–111.

Betteridge, B & Webber, S 2019, ‘Everyday resilience, reworking, and resistance in North Jakarta’s kampungs’, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, vol.2, no.4, pp.944-966.

Butler, J 2006, Precarious life: The powers of mourning and violence, Verso, London.

Butler, J 2009, ‘Performativity, Precarity and Sexual Politics’, AIBR. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, vol.4, no.3, pp.i-xiii.

Chatterjee, P 2011, Lineages of political society: Studies in postcolonial democracy, Columbia University Press, New York.

Colombijn, F 2010, Under construction: The politics of urban space and housing during the decolonization of Indonesia, 1930-1960, KITLV Press, Leiden.

Davis, M 2005, Planet of slums, Verso, London.

Foucault, M 2011, The courage of the truth (the government of self and others II): lectures at the Collège de France, 1983-1984, ed. A I Davidson, trans G Burchell, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK; Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Gibbings, S L, Lazuardi, E & Prawirosusanto, K.M 2017, ‘Mobilizing the masses: Street vendors, political contracts, and the role of mediators in Yogyakarta, Indonesia’, Bijdragen tot de taal-, land-en volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, vol.173, no.2-3, pp.242-272.

Guinness, P 1986, Harmony and hierarchy in a Javanese kampung, Oxford University Press, Singapore.

Guiness, P 2009, Kampung, Islam and state in urban Java, Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with NUS press, Singapore.

Guiness, P 2020, ‘Managing Risk in Uncertain Times’, Ethnos, vol.85, no.3, pp.423-434.

Herriman, N 2012, The entangled state: sorcery, state control, and violence in Indonesia, Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, New Haven.

Herriman, N & Winarnita, M 2016, ‘Seeking the State: Appropriating Bureaucratic Symbolism and Wealth in the Margins of Southeast Asia’, Oceania, vol.86, no.2, pp.132–150.

Hutchinson, J & Wilson, I 2020, ‘Poor People’s Politics in Urban Southeast Asia’ in The Political Economy of Southeast Asia: Politics and Uneven Development under Hyperglobalisation, Springer International Publishing, pp.271-291.

Kurasawa, A 2009, ‘Swaying between state and community: the role of RT/RW in post-Suharto Indonesia’ in Local Organizations and Urban Governance in East and Southeast Asia. Edited by Read, B. L., & Pekkanen, R. Routledge. pp. 68-93.

Kusno, A. 2000, Behind the postcolonial: architecture, urban space, and political cultures in Indonesia, Routledge, New York.

Kusno, A 2019, ‘Middling urbanism: the megacity and the kampung’, Urban Geography, pp.1–17.

Li, T 2007, The will to improve governmentality, development, and the practice of politics, Duke University Press, Durham.

Lont, H 2005, Juggling Money Financial Self-Help Organizations and Social Security in Yogyakarta, Brill, Leiden. Available from: https://brill.com/view/title/23404.

Millar, K.M 2017, ‘Toward a critical politics of precarity’, Sociology Compass, vol. 11, no.6, pp 1-11.

Mudhoffir, A M 2020, ‘Islamic populism and Indonesia’s illiberal democracy’ in Democracy in Indonesia: from stagnation to regression? Eds T Power, E Warburton, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore, pp.118-137.

Munck, R 2013, ‘The Precariat: a view from the South’, Third World Quarterly, vol.34, no.5, pp.747-762.

Murray, A J 1991, No money no honey: A study of street traders and prostitutes in Jakarta, New York; Singapore; Oxford University Press.

Neilson, B & Rossiter, N 2008, ‘Precarity as a political concept, or, Fordism as exception’, Theory, Culture & Society, vol.25, no.7-8, pp.51-72.

Newberry, J C 2006, Back door Java: state formation and the domestic in working class Java, Broadview Press, Peterborough.

Newberry, J C 2007, ‘Rituals of rule in the administered community: The Javanese slametan reconsidered’, Modern Asian Studies, vol.41, no.6, pp.1295-1329.

Newberry, J C 2008. ‘Double spaced: Abstract labour in urban kampung’, Anthropologica, pp.241-253.

Reid, A 2011, ‘To nation by revolution: Indonesia in the 20th century’, NUS Press, Singapore.

Savirani, A & Aspinall, E 2017, ‘Adversarial linkages: The urban poor and electoral politics in Jakarta’, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, vol.36, no.3, pp.3-34.

Scott, J C , 1985. Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Scott, J C 1998, Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Soemardjan, S 1962, Social changes in Jogjakarta, Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Standing, G 2014, The precariat: the new dangerous class, Bloomsbury, New York.

Sullivan, J 1992, Local Government and Community in Java: an urban case-study, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

Sullivan, N 1994, Masters and managers: A study of gender relations in urban Java, Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards.

Tilley, L, Elias, J & Rethel, L 2019, ‘Urban evictions, public housing and the gendered rationalisation of kampung life in Jakarta’, Asia Pacific Viewpoint, vol.60, no.1, pp.80-93.

Winters, J A 2013, ‘Oligarchy and democracy in Indonesia’, Indonesia, no.92, pp.11-33.

Žižek, S 2008, ‘Nature and its Discontents’, SubStance, vol.37, no.3, pp.37-72.