On Reconciliation Day 2024, I awoke and glanced at my phone, a habit I had fallen into, and I saw a call out from the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment Instagram account. A showdown had begun between ANU students and staff, and security officers and police over the Encampment. In past years I spent the day with friends, or attending music concerts with Aboriginal artists Briggs or Yothu Yindi. A combination of personal struggles, the genocide in Gaza, and the failed referendum left me feeling unwilling to mark the day. That sunny winter morning, I got a phone call from Rebecca, the partner of my good friend and sister in solidarity, Lina, who had been working with the students at the Encampment for some time. “We are organising support for the Encampment and trying to prevent further escalation. We need help. Please get in touch with Leah House.” She had lent her expertise from Tent Embassy activism and knowledge from elders and offered support to the Encampment. Together we discussed drafting a statement of support and agreed we would see each other in Kambri.

When I arrived on campus, I saw a throng of people in the usually sanitised commercial core of the university. People of all ages and backgrounds formed a ring around the central grass area where a core group of students had barricaded themselves and their belongings in the centre of Kambri. I spoke with undergraduate students from the Tjabal Centre who, like me, wore Aboriginal flag iconography. Sporting purple t-shirts were NTEU comrades whom I knew from my years as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representative on the ANU Branch Committee. I greeted colleagues, PhD scholars to Professors, dressed in casual weekend wear, sporting Keffiyehs, and some accompanied by their small children. The Professors were collectivising to put pressure on university management to call off the police. Their negotiating role would continue after this day, advocating for and lending credibility to the student activists. I saw retired staff members, university alumni, and community members alike joining in their support and protection of the Encampment.

Voices reverberated off the tall buildings surrounding the green, as people with megaphones led groups in chanting and singing. These included “We will not be moved!” and a chant I had heard adapted from use on other campuses in Melbourne and Sydney; “ANU we know which side you’re on, remember South Africa, remember Vietnam!” rang throughout the precinct. In these chants, students positioned themselves in relation to the longer activist history of the ANU and the student movements which took hold of Australia in the 60s and 70s. My mother, Liese Baker, arrived on her bicycle, sporting a hi-vis vest which I quickly encouraged her to take off to avoid being mistaken for a security official. She had studied at ANU from 1967-70 and was active in the movements today’s students were referencing, earning her an ASIO file like many activists of the period. After the police had retreated and the Encampment moved location, we reflected on Canberra’s shifting landscape of protest.

~

My grandparents came to Canberra in the 1940’s when Canberra’s development as the capital constituted an important part of Australia’s post war reconstruction policies. Coming from a Canberra based family embedded in the left-wing politics and activism of the post-WWII era, I have heard stories throughout my life of a time and place more vivid and exciting than the tame suburban reality I have known. These stories painted a picture of a landscape of protest; a landscape where bodies became tools of disruption, where calls for change and justice flowed through routes and spaces of the city, where alcohol, drugs, and sex coexisted alongside political discussion and strategizing. It was also a place where the state’s powers of surveillance were intimate and proximate, invading the home or disguised as a friend, neighbour or comrade.

My mum was one of the original four ANU labour club members who founded the (in)famous Canning Street activist house. They hosted the first meeting of Women’s Liberation in Canberra, organised against conscription, the Vietnam War, and apartheid South Africa. Early one morning, police raided the house in the successful pursuit of subversive poster making. The aesthetics of public space in the planned national capital must be maintained, regulated and sanitised of messages like “FUCK THE DRAFT”.

On Nardoo Crescent in O’Connor, my grandparents hosted parties where academics and feminists, pacifists and communists, post-graduates and undergraduates would spend time in a heady mix of politics and socialising. On the street at the top of the driveway, a man in a parked car noted number plates and wrote down names as leads for ASIO to follow up on in the paranoid mist of the Red Scare. Even spaces of hospitality became sites of political action. In the public bar of the civic pub, male dress codes were enforced, ties compulsory and women were excluded to the lounge. The women resisted, conducting sit-ins in a space where they were infantilised, and at Tilley’s café in Lyneham, the men were forbidden entry without a woman chaperone; the feminists were organising. The click on their phone calls told of the ears listening in.

Canberra’s roads became routes of disruption, paths from the university to Garema Place in Civic and across to Parliament House. Protestors, including my mother, grandfather, and uncle, blocked the road outside the US embassy, the first to be established in Canberra when the capital and government functions moved from Melbourne. Booked for traffic disruptions, a serious act in a city built around the motor vehicle, the women spent the night in Canberra gaol while the men were sent to Goulburn.

At the centre of many of these activities was the ANU, playing a pivotal role within Canberra’s landscape of protest. It was a place to meet, collaborate, and form solidarities, a base from which activists could move out into the community. The student residences would become a refuge for draft dodgers, including Steve Padgham, who was harboured by his girlfriend in Ursula Hall, a women’s only residence at the time. On- and off-campus, students, staff, and members of the public worked together to conduct teach-ins and counter-lectures on topics including the Vietnam War, the moratorium on conscription, and the purpose and role of the university. I was proud to hear today’s students referencing the actions of previous generations of ANU students.

~

Left out of the student chants and the stories I grew up on was the role of the ANU in the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1972. My mother had left the ANU and Canberra by the time the embassy was established, and I only learned of these connections since beginning my PhD which examines the ANU’s relationship with Aboriginal people.

This underappreciated and often unacknowledged history distinguishes the ANU from other Australian universities in its support for the longest running protest site in the world.

Though located in Canberra, the Aboriginal Embassy originated in inner-city Sydney in conversations between young Aboriginal people and an older generation of activists who had worked with the Federal Council of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) in campaigning in favor of the 1967 constitutional referendum. This generation sought to improve living conditions and provide equal opportunities by giving the federal government the power to make laws relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This intergenerational strategising took place in homes and pubs across Surry Hills and Redfern, which was becoming an epicentre of Aboriginal community and Black Power. Together, they considered how they could bring Aboriginal political voice and the land rights agenda to Canberra.

On January 24th of 1972, a group of 5 activists journeyed to Canberra from Sydney. Upon arrival they visited an unnamed ANU academic who provided them with a hot cup of tea and an umbrella. They would plant this umbrella in the lawns in front of Parliament House during that chilly Canberra night, and it would become the first structure of the Embassy. Drawing influence from the Aboriginal land rights struggles and adopting the politics of Black Power, the Embassy represented a coming together of regional and urban Aboriginal politics.

This growing protest site faced resistance from its earliest days and was threatened with demolishment throughout 1972. Movement of activists and students between the Embassy and the ANU would be essential for its survival. The National Council of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Women would be the first group to lend support when they walked from their Conference at ANU to the embassy on January 29th. They would lend the group of young men legitimacy and bring increased media attention to their action.

Other than the Gaming and Betting Ordinance, which imposed a forty dollar maximum fine for loitering in a public place, there were no laws to force the Embassy to disband during its early days. However, growing concerns for aesthetics and the need of Parks and Gardens attendant to mow and water the lawns for diplomatic guests, along with overt police surveillance, would create ongoing tensions. Members of the public and officials bemoaned the Embassy as an eyesore, a blight on the well manicured lawns of Parliament House.

As support for the Embassy and its calls for Land Rights increased through February 1972, the government was spurred to introduce a new provision under the Commonwealth Lands Ordinance to remove the tents. Meanwhile, ANU students and local activists would make contact with the embassy, and over 300 joined 60 Aboriginal activists for the opening of Parliament on February 22nd. The students provided financial support and established a radio link from the Embassy to the ANU union building for the purpose of rallying large numbers.

On July 20th, mere minutes following the publishing of the amendment to the Trespass on Commonwealth Lands Ordinance, 150 Commonwealth Police descended to take down the tents. The radio link was jammed, forcing students and activists to rely on telephone and word of mouth on campus. 70 protestors, made up of Aboriginal activists and non-Indigenous students and community members of all ages, were set upon, facing violence from what some described as a paramilitary force. Almost all the protestors were injured and some were arrested. The tents were pulled down and taken away.

This violence would be repeated days later and the ANU Health Service would treat those injured. The ANU Bar became a place for the activists to gather and strategise their next moves for reinstating the Embassy. It provided a space for Aboriginal activists to build relationships with white allies in their fight for self-determination. ANU Union was suggested as a space for negotiation between the Embassy and Nugget Coombs in his role with the Council for Aboriginal Affairs. The Embassy also provided the ANU with its two earliest known Aboriginal students, Gordon Briscoe and Pat Eatock, both of whom played central roles at the embassy and would go on to be important voices in Aboriginal activism and academia. The embassy was re-erected by September and its successes ranged from raising Land Rights to national debate and influencing Whitlam’s Labor Party platform in the 1972 Federal election.

~

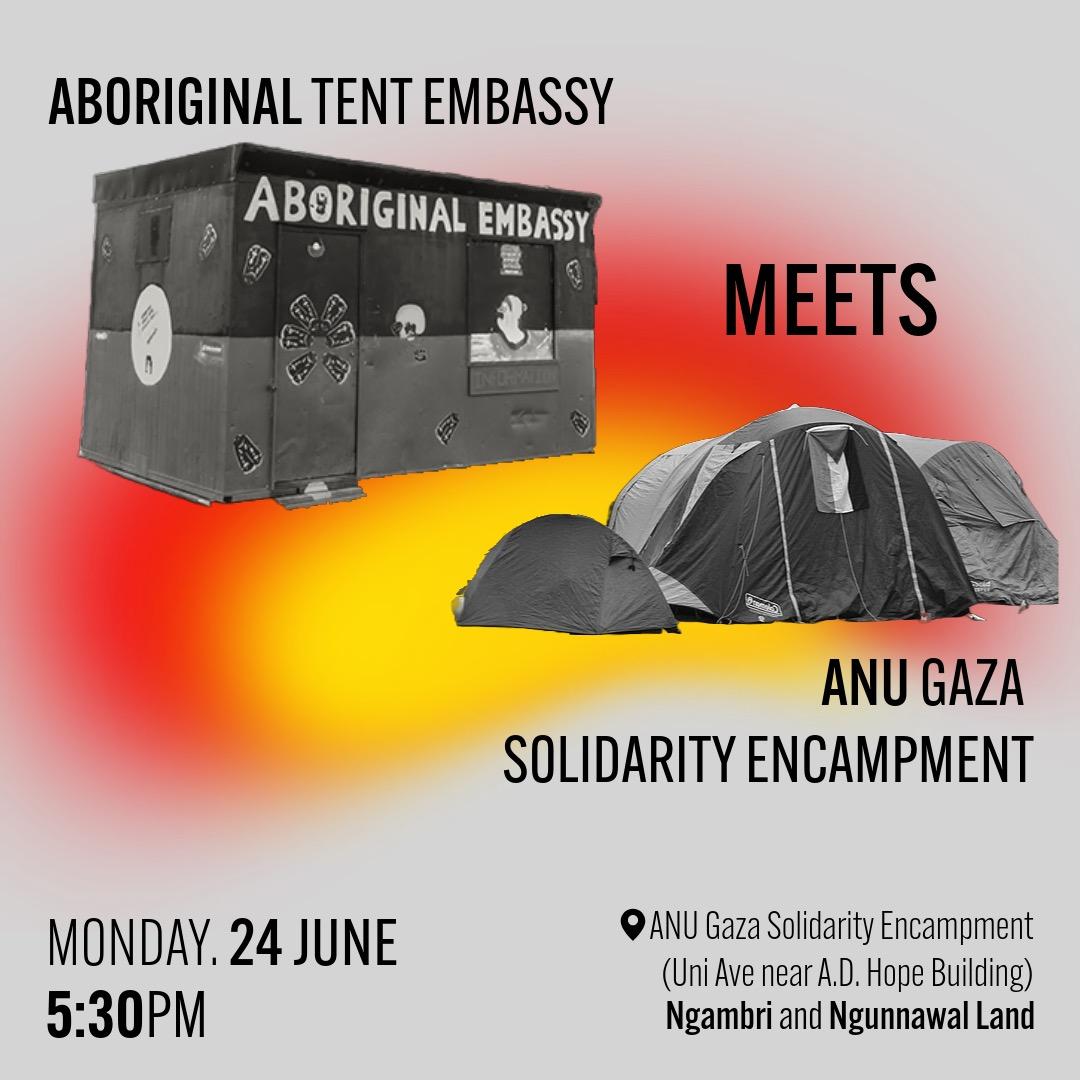

Much could be analysed in comparing the Tent Embassy to the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment; the role of elders and leadership, race and class privilege, social media and global discourse, the role of spirituality and not to mention the politics of occupying space on unceded, sovereign Country. One commonality which became apparent when comparing these occupations was the important role of the university in Canberra’s landscape of protest.

As Australia’s national university, the ANU is legislated to enable teaching and research “in relation to subjects of national importance to Australia” (Australian National University Act 1946). In service to these goals and the role of a national university, Walter Burley Griffin envisaged a university without hard boundaries where “town and gown” could come together and where the university could serve the people. Protest breaks down these boundaries and allows the university to serve the public beyond its financial interests and role in research and teaching. Protests such as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment brought the local community on to campus and facilitated relationship building between town and gown. These movements create spaces where the public felt they could belong and be invested in the university.

As ANU management plans its ongoing development of campus and aims to continue to create spaces of connection between town and gown (ANU 2019), it must consider the methods employed in regulating the use of public space on campus with reference to ANU’s broader role within Canberra’s landscape of protest.

ANU (2019). Acton Campus Master Plan. Australian National University. <https://www.anu.edu.au/news/all-news/acton-campus-master-plan>

Australian National University Act 1946 (Cth) no.22, s6

Briscoe, G. (2010). Racial Folly: A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family (Vol. 20). ANU Press.

Robinson, S. (1993). Aboriginal Embassy, 1972. [Masters Thesis] Australian National University. <https://kooriweb.org/foley/resources/history/newstuff2016/new%20folder/robinson_thesis_final.pdf>

Foley, G., Schaap, A., & Howell, E. (Eds.). (2013). The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State (1st ed.). Routledge.