I have been wrestling with this question for a long time, but the urgency of it has drastically increased since the beginning of the Gaza genocide. A series of events and experiences during the 2024 Gaza Solidarity Encampment at the Australian National University (ANU) threw into sharp focus the difference between artistic and cultural production as a tool for upholding the liberal status-quo and the repressive reaction of the cultural establishment, in this case the University, towards art-making and world-making it deems threatening and destabilising. As a recent graduate of the ANU School of Art and Design (SOAD), and as a person who hopes to pursue a creative life without compromising my own values, this piece is both my own testimony of the events that took place, and also part of my ongoing attempts to grapple with the implications of these experiences. I have come to understand the encampment as an exercise in collective world-making, and the most important creative project that I have been part of.

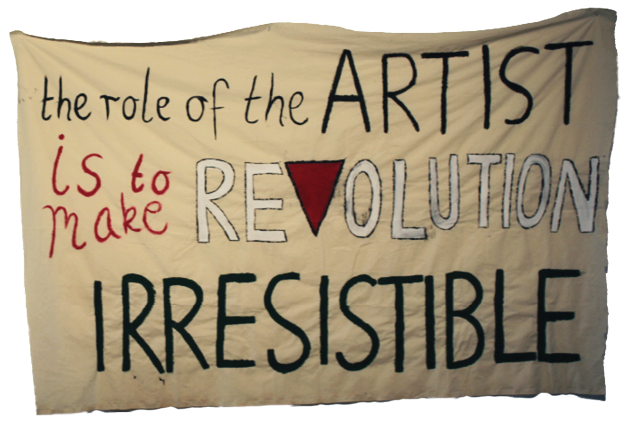

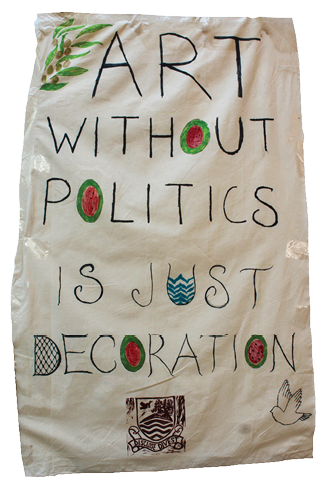

From the beginning, creativity and artistic expression was embedded within the Encampment, through handpainted banners and weaving circles, guitar jams and graffiti. Another article in this issue goes into greater detail about the creation of different kinds of art at the encampment, and how it managed to exist outside of and in contestation with the boundaries of institutional confinement. My article sits in dialogue with those ideas, while examining the ANU’s repression against pro-Palestine artistic expression by the Encampment through events that took place at the School of Art and Design.

On 11th June 2024, we, members of the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment, organised and installed a small exhibition in the Project Space, a display area in the foyer of the SOAD Gallery. The display brought together some of the banners, posters and other visual designs created by members of the Encampment, adorning the walls and hanging from staircases and ceiling rafters. We had gained permission to hold this exhibition, but it quickly became apparent that following official processes was not enough to protect us from the retribution of anonymous zionists, or the cold indifference of University administration. At some time between the completion of the exhibition installation and when the gallery space reopened the following morning, one or more individuals had vandalised and stolen works from the exhibition. Posters had been torn down, banners pulled from where they hung and removed, and Palestinian flags physically cut out from protest signs in a targeted and violent act of suppression, intimidation, and erasure. Despite searching through dumpsters across campus, we were unable to recover any of our artworks.

Two days later, SOAD made a public statement that “these materials were not removed by the University, nor the school”, and that “the University is investigating the matter to determine who may have removed and vandalised the materials.” However, the exhibition organisers were never informed of any outcomes of this investigation, despite numerous follow up attempts. This lack of accountability becomes particularly egregious when coupled with the fact that this vandalism occurred outside of working hours, in a building only accessible using swipe card access. The University is able to monitor swipe card records using their internal security system in order to determine which individuals accessed particular areas at certain times, something that we know is within the purview of the University. Via Freedom of Information requests, we obtained documents that revealed that pro-Palestine students at the encampment were monitored by the University in this way. However, the University appears not to take this same concern where anti-Palestinian racism is concerned. In fact, they capitulated even further to zionist interests during a subsequent meeting between exhibition organisers and SOAD management on the 14th of June, where we were offered the use of the space for a second exhibition, but only on the condition that the artworks would contain no references to Palestine or University ties to weapons manufacturers. In particular, the Palestinian flag was described as a “security risk” to students and staff.

In response to these events, the Encampment organised a protest on August 6th 2024. We gathered at the front of the art school, where I made a speech, along with several other students and staff. This was my first time speaking at a rally, although I’ve attended plenty of them. It is hard to describe exactly how it felt, both adrenalinising, and full of a deeply held catharsis in expressing my rage at a place that had, years ago, promised me creative emancipation, and then betrayed and broken that promise over and over again. After the speeches, we held a vote and unanimously decided to enter the Project Space and occupy it for the rest of the afternoon. We would create artwork in the space and mount our own guerilla exhibition, in defiance of the university’s censorship. We renamed this space to Shababeek Memorial Gallery in honour of the Shababeek Centre for Contemporary Arts which was the last remaining contemporary art space still standing in Gaza until it was destroyed by the Israeli Occupation Forces in early 2024, during the siege on the Al-Shifa Hospital (Kuta 2024). Inside, the space became alive with the hum of more than 50 people painting banners and fixing posters to the walls, surveilled all the while by university security staff. Later in the afternoon, after much of the crowd had dispersed, it was discovered by security staff that members of the protest had painted pro-Palestine slogans on the walls of the women’s bathroom. Those of us still in attendance endured a patronising lecture from the head of security about how we had greatly disappointed her, up until this point she had been “so impressed” at how we had conducted ourselves.

The last of us left the space at around 5pm. No more than an hour later, I returned to the space to discover that all of our artworks had already been confiscated from the space. The next day, a college-wide email was sent by the Dean of the College of Arts and Social Sciences, alleging that the sit-in had entailed “damage to buildings” and “vandalism”, and caused “disruption to work and study”, including “behaviour… causing harm to those in our community.” The Dean’s email on the 17th of August 2024 also stated that “Requests to install artistic exhibitions in University buildings must be made and authorised through appropriate channels and this did not occur in relation to yesterday’s incident.” This kind of authoritative, bureaucratic language belies a colonial rhetoric that condemns property damage and disruption to business as usual as worse crimes by far than the aiding and abetting of genocide. Furthermore, the Dean was making a deliberate, hypocritical obfuscation in failing to acknowledge that the genesis of the sit-in was the vandalism of our original exhibition, and the university’s subsequent refusal to investigate the incident or to offer us a follow-up exhibition.

Despite its ephemeral nature, the Shababeek sit-in, much like the Encampment itself, demonstrated to anyone paying attention the exact nature of the University as a colonial, zionist institution, one that cares much more about paint and nails on walls, and about the appeasal of zionist feelings, than it does the lives of Palestinians. The University had no hesitation in weaponising carceral disciplinary frameworks under the guise of “psychosocial safety” in order to suppress pro-Palestine sentiment and punish individuals, claiming that slogans such as “long live the Intifada” were distressing to some staff and students, and thereby breaching the University’s duty of care under work health and safety laws. This is just one example of the structures of censorship and suppression that we see again and again in this colony whenever artists, writers and creatives speak up for Palestine (Marsh 2025). None of this is coincidental, but rather a deliberate, structural tactic of silencing and isolation, which acts as a deterrent to others, particularly in the arts, who are intimidated by the threat of professional punishment and blacklisting from career opportunities in an already precarious sector.

This threat is something that hit home all too closely for me during the Encampment. I still hesitate to call myself an artist, but I started a job at a national cultural institution less than a month before the Encampment began. This institution’s stated purpose is to promote diverse forms of creative and artistic expression and cultural identity, but as an employee whose job comprises front-facing engagement with members of the public, I am constrained in the extent to which I can express my personal views. My personal identity is sublimated into an institutional structure where visitors perceive me not as an individual but as a personified extension, a mouthpiece, of the institution.

I felt this dissonance acutely on the days where I would wake up in a tent in the middle of campus and get dressed in my uniform to go straight to my job at a national cultural institution. I would emerge from my tent in the early morning, surrounded by mist and the silence of an empty campus, but later on I would be consumed with anxiety by the possibility that someone had seen me leaving the encampment in a shirt emblazoned with the name and logo of my workplace. Even writing this piece over a year later, I hesitated to put my name to this article in case it is somehow traced back to my employment, and I face consequences for failing to remain impartial in accordance with the public service code of conduct.

A few weeks after the Shababeek sit-in, we held another action at the opening of the School of Art and Design Drawing Prize on the 28th of August 2024. As the head of the Art School began his speech before announcing the winners, camp members laid down on the ground in front of the lectern in the style of a die-in, while five students held up signs:

ANU IS COMPLICIT IN THE GENOCIDE IN PALESTINE

WE WONT BE SILENCED INTO COMPLICITY

SOAD IS CENSORING STUDENT PROTEST AND BLOCKING DISPLAY OF THE PALESTINIAN FLAG IN THE GALLERY

WE WILL DISRUPT BUSINESS AS USUAL WHILE THE ANU SUPPORTS ISRAEL’S GENOCIDE

OUR DEMANDS:

→ FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND POLITICAL EXPRESSION

→ PROVIDE A NEW EXHIBITION DATE

→ RESTORE ACCESS TO GALLERY

→ CUT ALL TIES WITH WEAPONS MANUFACTURERS, COMPANIES AND INSTITUTIONS THAT SUPPORT ISRAEL’S GENOCIDE IN GAZA

There was a long, crackling silence in the space as we all moved into place. Finally, the director of SOAD addressed us directly from the lectern:

“Are you finished?”

“We aren’t stopping you from speaking.”

We remained in place, silently remaining in place on the floor and holding our signs, for the entire duration of the speeches. I watched and filmed from within the small crowd, with a mounting sense of incredulity at the stubborn refusal of the speakers to acknowledge our presence. Flanked on either side by silent protestors against the cultural erasure of indigenous Palestinians, the director of SOAD made an acknowledgement of Country in which he spoke about his observations of the wattle blooming unseasonably early on Ngunnawal Country as a result of anthropogenic climate change. This was a note-perfect replication of the dynamics of liberal culture’s self-congratulatory virtue signalling, alongside a stubbornly wilful blindness towards its own active complicity in ongoing imperialism and genocide. It felt like an almost comedically on-the-nose piece of immersive, participatory performance art.

Now I return to my original question: how can those of us in the imperial core make art and do art-making as a liberatory practice? On one level, it feels almost obscene to ask these questions, particularly filtered through the prism of my own personal experiences and anxieties, when positioned next to the sheer scale of the genocide. On another level, I do believe that there wouldn’t be such an institutional-wide crackdown against pro-Palestine cultural production if it didn’t hold power. I also believe that the line between art-making and acts of resistance is not as clear cut as those in power would like us to believe. Making art is fundamentally about envisioning and creating something new, through iteration, experimentation, trial, and error. The work of the artist is never finished, there are always future possibilities, choices and directions to expand and grow, new worlds to create. This is a lot like the work of creating the space of the Encampment. Over time, I have come to understand the existence of the Encampment itself as a kind of public, participatory installation. It was an intervention into public space, a disruption of the ordinary and an exposure of the systems of institutional power and violence that are usually hidden below the surface. It was also an intervention that did not exist in isolation, but as one part in a much larger ecology of other Gaza Solidarity Encampments across the world.

Here, I refer and defer to the work and words of Black culture workers, particularly Ismatu Gwendolyn in her essay “the role of the artist is to load the gun” (2024), which in turn references Toni Cade Bambera and her quote:

“As a culture worker who belongs to an oppressed people, my job is to make the revolution irresistible.”

Crucially, Gwendolyn raises the important distinction that Bambera makes in her broader speech, that while her job as an artist is to make revolution irresistible, this role is intertwined with her position as a member of an oppressed people. The mere fact of art-making, of world-making, is not in itself inherently liberatory. Many artists and their work exist to uphold the liberal status quo, to confine our imaginations to the type of world-making that most benefits the colonisers. The threat of punishment and isolation by the establishment functions to coerce our obedience, manipulate us into remaining within the comfortable bubble of liberal respectability politics that celebrates performative allyship but condemns property damage as violent. For settler artists, including myself, this seductive, insidious trap of this colonising rhetoric must be continually and actively resisted. We must remain constantly alert to new manifestations of this placating, colonising rhetoric within our own minds, not out of guilt or self-flagellation, but as an active, continual choice of love and resistance.

In the aftermath of the encampment, many of us shared our experiences of how incredibly jarring it felt to return to “normal” life. The stifling structure and rigidity of workplaces and classrooms, the isolation and loneliness during something as mundane as an evening meal, the cognitive dissonance and sense of distance that arose whenever we tried to have a conversation with anyone who had not shared our experience at the encampment. And the genocide continued, and continues, unabated. At times, it was difficult to escape the feeling that everything had been for nothing. Frustratingly, many outside observers had been taken in by the University’s highly publicised but essentially meaningless “changes” to its Socially Responsible Investment Policy, but in reality, the University had refused to divest or take any meaningful action in accordance with our demands.

During the Encampment, pro-Palestine graffiti stubbornly appeared and reappeared at various sites across campus. It clearly bothered the University enough that they went to great lengths to remove it, but in one instance, near the end of the Encampment’s duration, their insistence in erasing it backfired. They used a pressure washer to remove spray-painted messages and drawings from a paved area on the edge of campus, an area known by members of the Encampment as the “Spiral”. However, this particular part of public space had been ignored for so long by the groundskeepers that the pavings had turned a dark grey colour. The pressure washer didn’t just remove the gold spray paint, but also these accumulated layers of build-up and grime, exposing the original beige colour of the bricks. Once again, in their haste to obliterate any trace of dissent, the University had created an ironically conspicuous artifact of the dynamics of erasure, one that looped all the way back around to visibility. More than a year later, these marks are still visible, defiant traces that remain for anyone who cares to look.

Gwendolyn, I. (2024). the role of the artist is to load the gun. Threadings. <https://www.threadings.io/the-role-of-the-artist-is-to-load/>

Kuta, S. (2024). ‘Arts Center in Gaza Destroyed in Israeli Hospital Siege’. Smithsonian Magazine. 12 April 2024. <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/arts-center-in-gaza-destroyed-180984142/>

Marsh, W. (2025). ‘Speaking out on Gaza: Australian creatives and arts organisations struggle to reconcile competing pressures’. The Guardian. 15 June 2025. <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2025/jun/15/speaking-out-on-gaza-australian-creatives-and-arts-organisations-struggle-to-reconcile-competing-pressures>