No work reflecting the Australian National University (ANU) Gaza Solidarity Encampment would be complete without stating first and foremost our unequivocal support for Palestinian liberation. We will always stand in solidarity with Palestinians in their struggle against settler colonialism, as we stand with First Nations people here in so-called ‘australia’ and around the world. Since the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment, so-called ‘israel’ has only accelerated their genocide in Gaza, as well as their ethnic cleansing campaign in the West Bank. The ANU remains complicit in ‘israel’s’ crimes, just as they are complicit in the systemic oppression of Indigenous people here at home. Both authors are writing this work on stolen, unceded sovereign lands of Ngunnnawal and Ngambri peoples. We express our solidarity with the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples and believe there can be no justice or peace on stolen land under ongoing colonisation and occupation. Whilst we reflect on the Encampment we also must commit ourselves to continuing to fight for Palestinian liberation, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ liberation, and for liberation for people everywhere.

Art and the creation of art was a foundational part of the Encampment. In many ways, it defined the spaces we lived in. It extolled our demands, set internal tone and expectations, and it was used to spread the Encampment movements’ messages and ideals. The ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment was a space in a suppressive university where students and staff could freely propagate ideals of Indigenous solidarity, anti-colonialism, and anti-capitalism, and art was a core tool in the construction of such a space. In this work, we seek to discuss the political and personal experiences of art stemming from the Encampment through telling the stories of the works that made up the Physical Encampment space and its surrounds. Both publicly and privately, art was foundational to life at the Encampment. This is highlighted in both authors’ personal reflections on the time.

Please note that of all the activities of the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment none exemplify the collaborative nature of protest art, the collective effort needed for its installation, and the restorative nature of occupying a reclaimed space more explicitly than the Shababeek Memorial Gallery. This short-lived exhibition, held on the 6th of August 2024, merits an article of its own and

is beyond the scope of this one. Instead we wish to draw a focus to two spaces transformed by protest art: the spiral

with graffiti and the Encampment itself with banners.

Mio

With one exception, all of our banners were handpainted on fabric. I contributed to a few, though I was not involved in the majority produced within the encampment. When I did participate, however, the process was deeply collaborative. Each banner bore the imprint of so many different hands before the paint had even dried. Installation, too, often required tools and additional teamwork. Whether hung inside the camp or facing University Avenue, the banners transformed the space. Internally they set expectations and reflected shared rhetoric; some were kept inside because their external display risked conflict. Externally, banners were billboards to passing foot traffic, largely free from media distortions. Space constraints on Kambri Lawn sometimes limited how many could be displayed. Decisions about which banners were displayed, stored, retired, or even stolen (probably a story for the Shababeek Memorial Gallery article) were highly politicised, shaped by organisational affiliation and disagreements over optics. They remained central to situating ourselves within the context and declaring why we were there.

By the time a banner was staked into a garden bed facing University Avenue, it had usually passed through many hands. When the paints came out, several banners were often made at once. Each began with a single person’s idea, then grew collectively. From phrasing, we moved to the sketchbook, where typeface, colours, composition, and imagery were decided. A section of calico, always cut longer than expected, was then prepared. Chalk outlines transferred the composition onto the banner. I often used multiple layers of chalk in different colours before passing the work to others with brushes and acrylic paint. Given their size, banners used up large amounts of paint, with four or more people sometimes working simultaneously. Variations in handiwork left traces, two shades of red meeting mid-word, or one painter’s streaky line beside another’s sharp edge. Once painted, everyone had to guard against stepping on the banners as they dried in our crowded main tent thoroughfares. Hanging the banners required strong clips to attach them to the gazebo. Staking demanded at least one guy on the stake driver, then at least two people pulling the banner to tension, and another guy on the staple gun. In times of desperation, we used hammer and nails.

Simply making banners was an act of grieving together while acknowledging the genocide. The act itself reclaimed space. Displaying them gave us control of the narrative around our Encampment. For me, there were times that it felt rejuvenating to be amongst the art made by other people not conceding to the “business as usual” agenda. Their visibility reminded other people on campus of the ongoing genocide. There was no ambiguity as to what our impetus was in setting up the tents.

Some of the banners were slashed by passersby. This retaliation acknowledges the power of our messaging, though the banners alone were not the target. Rather, the vandalism reflected the dissonance between the reality of genocide against Palestinians and dominant Western media narratives. The art we created and displayed and the reaction it provoked situated us firmly within the global pro-Palestinian movement.

The banners were also sites of internal conflict. Early on, disputes over messaging led to the removal of the ‘Intifada Intifada’ banner adorned with the Palestinian flag from public view. This decision came from those who feared Arabic text would draw racist backlash, though such capitulation never earned kinder treatment from the media.

The politics of banners extended to who made them. This was especially pronounced when any specific organisation was included on the banner. A lot of banners were made prior to the Encampment’s launch and were brought in by different groups. As individuals and clusters withdrew, they often took their organisations’ support with them. After the move from Kambri Lawns to University Avenue, we found ourselves with banners bearing group names without any members still present. Having material explicitly affiliated with other organisations was a point of contention on camp. This created dishonesty and confusion, as it implied unity behind groups no longer represented. Judgements and preconceptions of such groups frustrated many participants and tainted the way onlookers perceived the Encampment and its operations. When those organisations left, we seized the chance to create unbranded banners. These banner paintings occurred during the winter break, where numbers at camp had dwindled. Fewer people made the art process more intimate.

Pip Grimshaw

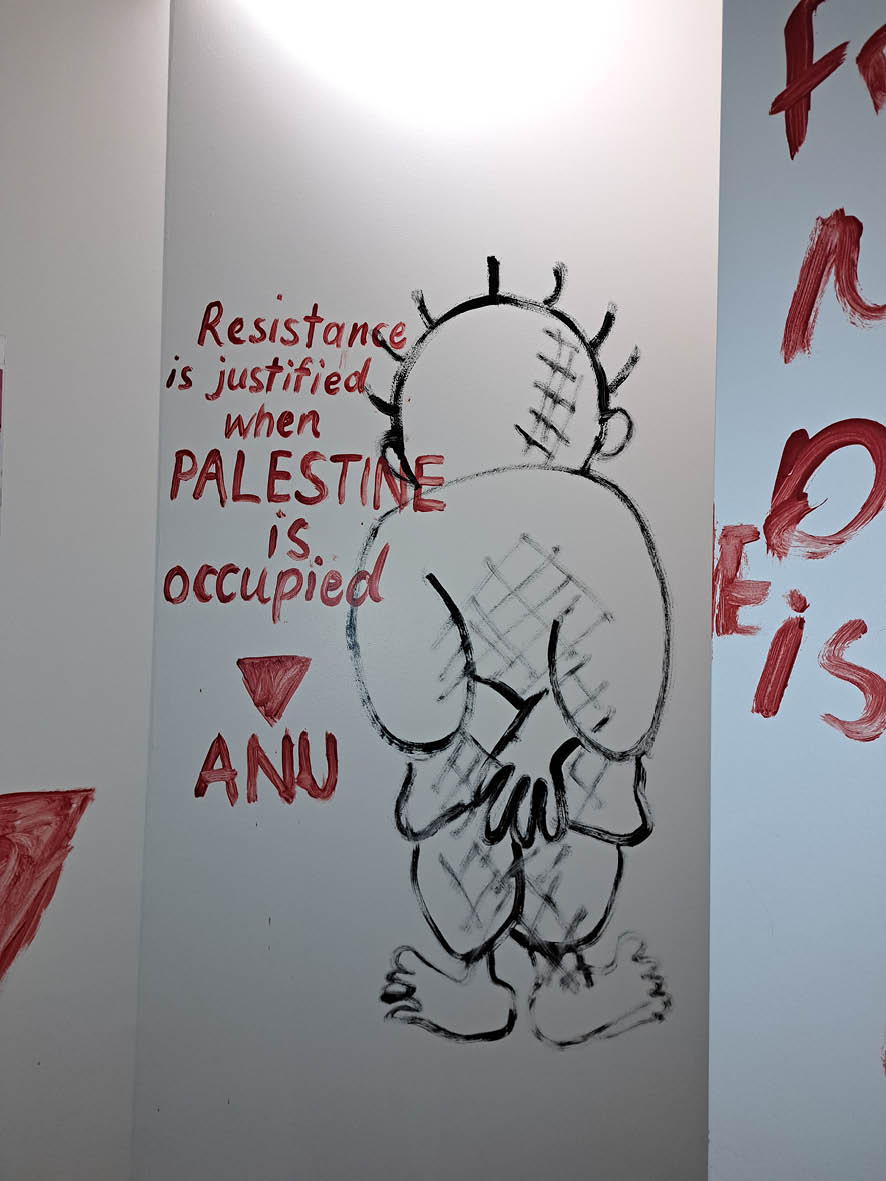

At the edge of the ANU campus there is an area dubbed ‘the spiral’. It consists of spiraling brick walls with descending levels meeting at a grate in the middle. For me, the spiral became the place where the intersection of community and art became truly tangible. On those plain brick walls, many people painted messages of support for Palestine, for First Nations People, and other struggles against oppression. Frustrations, anger, hopes, and ideals were inscribed into the physical space. Over weeks, new pieces appeared, sometimes overnight, so that campers on smoke breaks would find the spiral transformed.

The art faced inward, not positioned to be visible or designed to make a grand public statement. In this sense the graffiti in the spiral differs from many of the banners erected at both Encampment sites. Whilst the spiral was undoubtedly a public space—we would often go to sit there and find it occupied by the broader people of Canberra—this is not what it represented for Encampment members. Rather, for the Encampment, the spiral was perceived as a private and intimate community space, a place to withdraw from the inherent exhibition of living at the Encampment.

The works included “all eyes on Rafah”, “from the river to the sea”, “no re-plastering the structure is rotten”. There were drawings of watermelons, Palestinian flags, the land mass of so-called ‘australia’ with the Aboriginal flag overlaid. The artwork grew and developed, changing as each new artist brought their own experiences, skills, and vision to the wall. Before the original collage was removed, the walls of the spiral had become a visual testimony of defiance against the university both on an individual and collective level. It also excised and memorialised collective convictions and angers, hopes and beliefs. The works of the individuals came together on the walls as a collective creation. The art reclaimed the space; it made it ours, made it the broader communities’. It was a reclamation and reappropriation of campus at a time when the university’s draconian suppression of pro-Palestinian speech closed all institutional channels for artistic expression. Artists had been banned from displaying pro-Palestine works. The ANU’s School of Art and Design had banned Palestinian artworks, while tolerating zionist vandalism without any consequences. Despite these restrictions, the spiral offered a channel for the movement’s artistic voice. The process of creation allowed people to release their pent-up emotions. The presence of art helped create a sense of security for students confronting a hostile university. The spiral was imbued with traces of not only each artist, but of every person who spent time there, smoking or just resting away from surveillance. With every new work of art, story, shared laugh, and joke told to misty laughs, the space became animated with life. Through art and community, the physical space of the spiral gained meaning, and heart.

There are so many memories from this time connected to the spiral, set amongst the unseen development of the art inside. It is where we would go to smoke and connect with each other. There were birthday drinks, late night darts, and midday chats. It was where we went to take a moment away from the near constant surveillance and chaos of the Encampment. The space felt connected to the Encampment and those there were bonded by it, but it was also physically away from the tents. The artwork only deepened this, transforming the university’s empty lifeless structures into a living symbol of anti-colonial solidarity.

The spiral’s role paralleled that of the Encampment itself. Both were spaces built within and in spite of a hostile institution, the presence of both were forms of visual challenge to the ANU. However, the Encampment was a deliberately prominent, visible space. It was purposefully striking, open to the public and the university. This is a stark juxtaposition to the spiral, which felt more like a hidden enclave.

After the University has washed away the paint, I still think about the spiral’s beauty. A blank wall is no more neutral than a painted one; both are political. The ANU’s obsessive cleaning of the spiral hasn’t managed to get rid of everything. A dash of paint here, a splash of colour there, these marks remain steadfast tributes to when those bricks came alive with the feelings and expressions of the community. The ANU could not let us claim that space. They couldn’t let us communicate our experiences, even in a little used corner of the university. Even though the art was done in a mostly empty area, they felt the need to repress the artistic expression of those who opposed them and their genocide enabling policies. However, in their attempts to return the walls to their stagnant beginnings, they miscalculated the ways in which we had become connected to the space. It was ours now, and the remnants of the artwork which refused to be scrubbed away remain as a symbol of our connection to this strange, liminal space.

Towards the end of the Encampment, a number of people returned to the spiral to create art. The atmosphere at the camp towards the end was strange; people were exhausted, we didn’t have electricity any more, ANU Security were conducting disruptive ‘welfare checks’ at any hour of the night. Additionally, as someone who helped with the Encampment media team it had become almost unbearably frustrating and demoralising watching our university blatantly lie about so many things to local and national media. At some point all these feelings were going to boil over, and it’s a testament to all the artists in the movement that people found a way to use these experiences to create and bring people together. On their return, people did not recreate what had been there. Instead, new artists brought themselves to the canvas, and returning artists were informed by the overwhelming events that had occurred since the spiral was last painted. As a display, the art in the spiral was profoundly moving to me. It made tangible the power of art as community building, it showed how art can fundamentally transform spaces into places of solidarity, care and humanity.

They may have washed away the paint, scrubbed the walls, but they could not erase the experiences we shared as a community in that space. Art can be repainted; bricks can be scrubbed down but the connections and the feelings of belonging that the collaborative art created will never be forgotten.

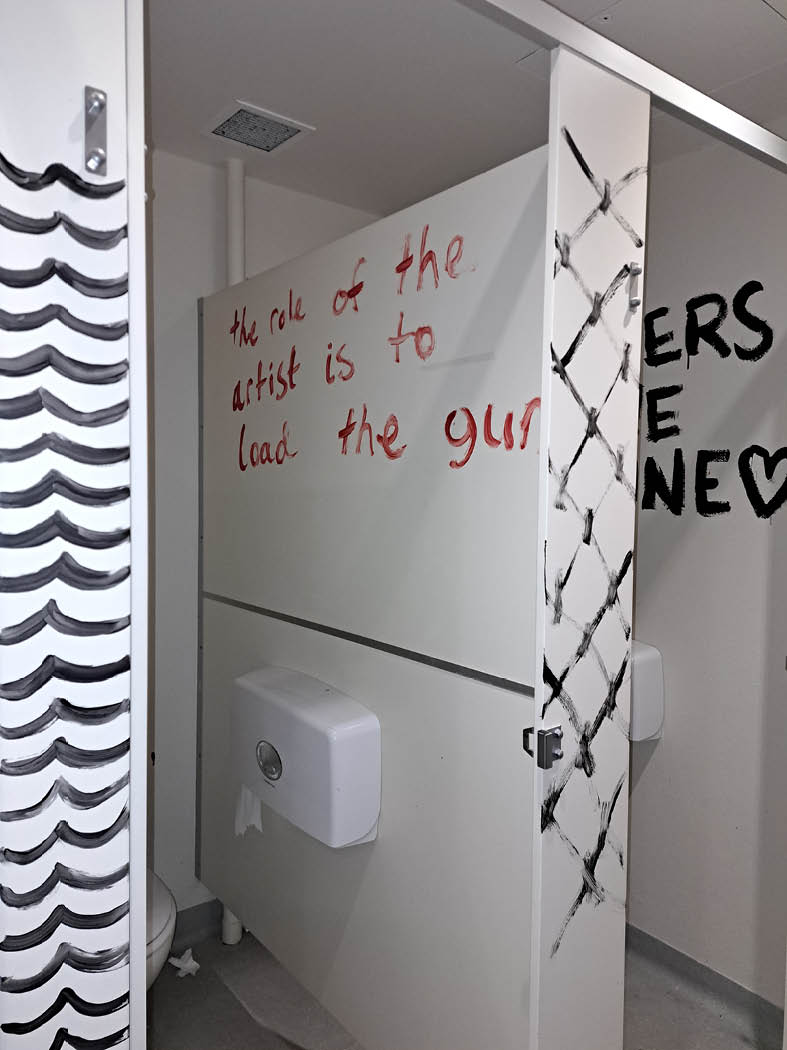

By reflecting on some of the art created during the ANU Gaza Solidarity Encampment, I can’t help but note the radical potential baked into both the messages conveyed, and the process of their creation. Art was used to challenge the ANU’s complicity not only in the genocide of Palestinians, but with their support for the broader structures of imperialism, colonialism and white supremacy. Not only was art used to represent the protestors’ opposition to the university, it also became a core part of community building. Toni Cade Bambara once said “the role of the artist is to make revolution irresistible.” I would add: the role of the artist is also to make revolution bearable, bringing the community together, providing an emotional outlet, and helping to create spaces of safety (or perceived safety) within the dominant systems of hostility and suppression.

Art lay at the heart of the Encampment’s foundations. It defined where we lived, extolled our demands, and in the act of its creation it brought people together as a collective. Through the stories and experiences of that time, we hoped to have shed light onto the influence of art on both the physical spaces of the Encampment, but also on the community that sustained this movement. Internally, the art reflected evolving beliefs, ideals, values, and principles. Though we arrived with very different levels of artistic experience, both authors saw how essential art was to shaping the community we built. From the healing and affirming process of collective creation to the way art transformed Encampment spaces, the movement was shaped and defined by art. Through banners and graffiti, our presence at ANU became a stark visual reminder of the Palestinian struggle within the broader university community.