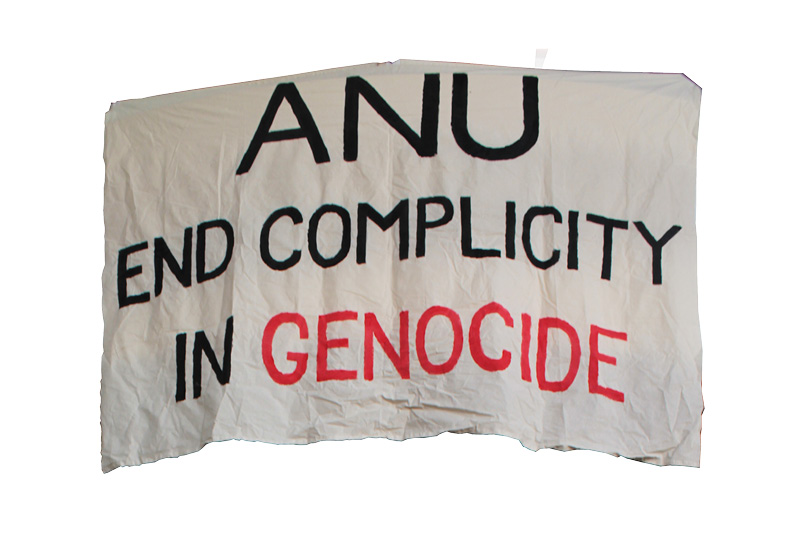

On April 29th 2024, we held our first Gaza Solidarity Encampment meeting on the balcony of the student union. As that day came to a close, many of us were zipping up our tents and wriggling into our sleeping bags. Inspired by students at Columbia University in New York, we joined the growing movement of University Encampment action that helped make Palestine solidarity ‘the largest mobilization triggered by a foreign event since the Vietnam War’. Moved by our growing understanding of structural complicity in Israel’s profound and explicit destructive violence against Palestinians, we instantiated our calls to boycott, divest from and sanction the Israeli apartheid regime. In constructing and indefinitely occupying a physical space at the heart of campus, we were rejecting ‘the invisibility of this genocide’.

I locate the Encampment in the global socio-historical situation that made it necessary and possible. The growing imperial-hegemony of the ‘military-industrial-academic complex’ (or ‘MIAC’) has emerged alongside a tradition of student and faculty resistance. I illustrate the stark corruption, hypocrisy and complicity of increasingly neoliberal tertiary institutions. Globally, the demands of boycott, divestment and sanction from dozens of Encampments have not been met. Sketching the scale and stakes of our national institution’s political and economic investments in imperialist violence shows the size and strength of what we were up against. On another level, the deep interdependence of the MIAC renders it vulnerable to mass action, underscoring the imperative to continue resisting imperial violence and its corporate war machines. Anti-imperialist and anti-colonial student actions, from the 1960s to now, have raised our collective political consciousness and built organising experience. Through describing the avenues through which our governments and universities have sought to disempower and disengage student activists, I argue that this demonstrates that we do pose a legitimate threat to the MIAC; that we can and must challenge it.

Universities are not neutral sites of knowledge production, but have become increasingly implicated in imperial and colonial violence which is tied to military-industrial projects. Over the course of the 20th century, the social role of the University transformed from a means of reproducing an educated elite to a mainly state-funded public institution promising social mobility and democratising intellectual and political development. The 1980s marked a turn ‘toward neoliberalism, with its bracing agenda of privatization, deregulation, tax cuts, management power, and short-term profit’. As Australia de-industrialised, our national economy became dominated by mining, leaving little need for autonomous knowledge-production. Casting ‘vice chancellors and their staffs... as entrepreneurs’, colleges of advanced education were merged into Universities in an effort to cheaply expand. State funding, which had provided a level of insulation between intellectual activity and capital interests, had fallen to 45 percent of University budgets in 2015 from 90 percent in the 1990s. The majority of funding now comes from student fees and private corporations. Universities have been forced to raise student intake, outsource, casualise and cut staff. Universities have invited private funding for research and teaching programs, determining research interests and ‘becoming virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity’; increasing proportions of University budgets are now funded by the defence sector.

While corporate funding arrangements are opaque, it is clear that MIAC are ever more interreliant in the neoliberal age. As Sian Troath argues, ‘each need[s] the other – for military advantage, for profits, and for survival’. The government ‘sees both strategic and economic value in militarization’, enhancing international strategic ties and promising national productive growth through these lucrative industries. Defence is already an economically integral sector in the US, and Australian universities are increasing their investments in the defense sector, seeking to support our employment and industry by emulating ‘Military Keynesianism’. Having come to rely on foreign suppliers, the Australian government announced in 2017 its explicit goal ‘to become one of the top-ten defence exporters [in an effort to increase] strategic advantage and economic prosperity’. At ANU, three different weapons manufacturers, whose products are purchased by Israel and the US to be used in Gaza, offer scholarships, paid internships, and postgraduate employment with loan repayment benefits. Two of these, BAE Systems and Northrop Grumman have stated aims to expand their academic partnerships in Australia and build our domestic industry.

Australia’s 2020 ‘Defence Transformation Strategy’ highlighted the ‘impact of COVID-19’ as providing ‘an opportunity to position defence research as a long-term business proposition to attract and retain experience and corporate knowledge’. In 2021 the number of contracts issued from the Department of Defense to Australian Universities was four times that of 2014: the highest it has ever been. When measured by monetary value the growth is ‘roughly eight-fold’. In 2022, ANU leadership proudly committed to partnering in the AUKUS deal to help develop nuclear submarines despite community protest. AUKUS entrenches Australia’s economic, military and political dependence on the US and UK and forces us to step into line with their geopolitical agenda, regardless of the public interest. That same year, Universities Australia went so far as to make ‘a public submission to the 2022 Defence Strategic Review’ explaining how they could make themselves useful. New institutes and centres for developing military technology have been forming since 2011 and partnering with dozens of universities across the country.

The proliferation of these institutions gives defence industries undue influence over our knowledge production sector. Worse still, increasing militarisation ‘driven in large part by the MIAC, contributes to regional tensions and fuels… competition it claims to be responding to’. Regardless of whether or not strategic circumstances warrant it, continual exorbitant defense spending must be perpetually justified. As economies become increasingly dependent on weapons production, they come to rely on sustained demand for arms and thus upon unspeakable death and destruction.

Solidarity Encampments are part of a larger movement calling to Boycott, Divest and Sanction (BDS) Israel. It is a direct legacy of the South Africa BDS movement that economically isolated South Africa and successfully condemned the apartheid regime. Similarly, ANU’s encampment was built on the historical legacy of ANU students working against our government’s complicity in imperialist regimes.

Over the course of 2024 we held ‘teach-ins’, where faculty and community members joined us in our central gazebo to teach us language and culture, as well as about settler-colonialism, imperialism and their persistence today. In July of 1965, ANU student protesters hosted a teach-in against the Vietnam War. ANU students continued to protest, rallying outside the hotel in which Lyndon B Johnson stayed on a diplomatic visit in 1966. In 1969 they rallied against conscription for a week. In 1970 they cancelled lectures to ‘participate in a national moratorium against Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War’. In 1970, thirty-five students were arrested and charged over their actions in the ‘Day of Rage’ demonstrations. Today’s Student Encampment movement has been global, following the historic Columbia University approach in making ‘the university a centre of protest against the Vietnam war when they occupied buildings in 1968’. Together with activists at dozens of universities in the Global North, anti-war students initiated a tradition of campus occupation. That same year, 1968, a group of ANU students travelled to Naarm to support the struggle for Aboriginal land ownership, continuing a legacy of resistance to protest land-theft and neo-colonial expansion. The movement for Palestinian liberation is fundamentally decolonial, grounded in an awareness of our own settler-colonial state, which continues to treat Indigenous people as second-class citizens and seek to extinguish their sovereignty. In March of 1971, ANU students held a vigil at the South African High Commission. Carrying signs such as ‘toot against apartheid’, hundreds of students maintained the action around the clock for ‘many months’.

The later privatisation of the University was more than a cash grab: it sought to undermine left-wing political dissent at a key site of its instantiation. It too was met with resistance: in 1994 over 150 student activists occupied the chancellery building for more than a week, as part of their ‘No Fees’ campaign. They were ‘removed by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) who used chainsaws’ to enter the building. In 2001, students staged an occupation of the ANUTECH building to protest increasing corporate sponsorship. While introducing further avenues for corporate interests to promote their political-economic agendas, the introduction and escalation of punishing student debt transformed the purpose of pursuing higher education. Students can no longer view themselves

as developing critical democratic subjectivities. Instead we are obtaining qualifications necessary to raise our individual value as human capital. This raises the stakes for student activists: our future security is profoundly threatened by institutional retribution.

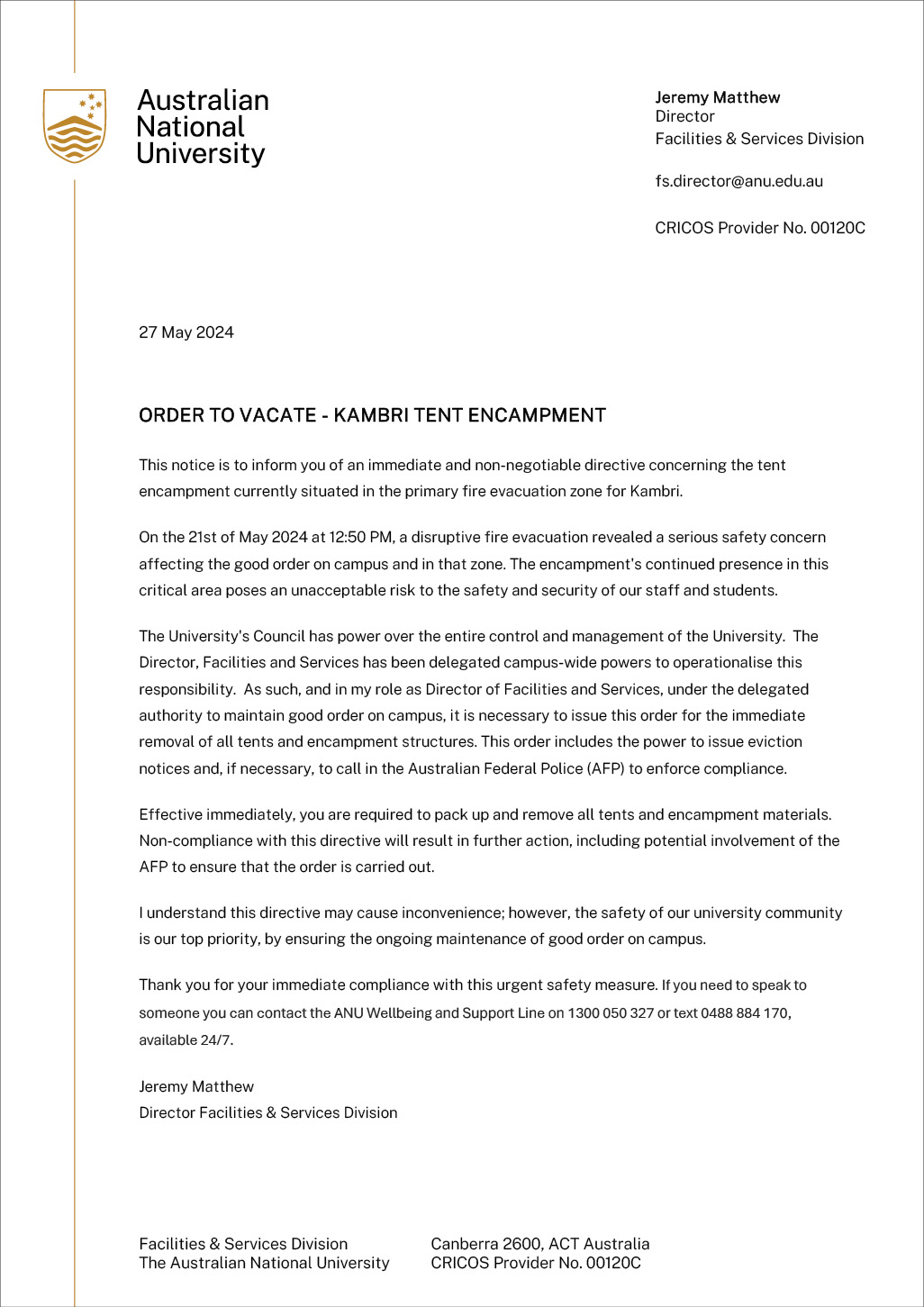

On April 18 2024, just the day after it was erected, the police were called onto the Columbia Encampment by their University President, who cynically cited her decision to be related to a concern that if the university didn’t enforce boundaries between free speech and harmful speech then the government would do so in their place. Instead, she not only exposed the institution to criticism it had capitulated in anticipation of State repression, but invited State forces into their space of teaching and learning. The following day, hundreds of Columbia staff walked-off in solidarity with the students. Similarly, on 27 May, the police were called to assist ANU security in vacating the Gaza Solidarity Encampment, citing ‘safety risk’. As at Columbia and other encampments globally, we were formally and informally supported by faculty and union members. Staff, via the National Tertiary Education Union, were also already fighting the effects of neoliberalism.

As at other universities, the ANU University leadership is prepared to celebrate its ‘long and feisty history of activism’. Simultaneously, they elide its contemporary opposition to movements that were often critical of the institution itself. Vice-Chancellor Bell’s statement in the 2024 Annual Report praised the University’s ‘proud tradition of student activism [and committed] to ensuring that such expressions occur within a framework of respect and safety’, despite soliciting state force, expelling two students and threatening a dozen others for their ‘diverse perspectives’ and ‘engagement with global issues’. As protestors have developed means of challenging its reach, the MIAC has been developing its own playbook of quashing dissent. They use hard power, such as the real or potential threat of state violence, and they use soft power to attempt to define the bounds of acceptable political speech. Over the 110 day occupation ANU leadership issued bad faith statements about student safety and damage to the lawns. They called students into private disciplinary meetings where they tried to elicit information, threatened expulsion and expelled students over political speech. They used intimidation and surveillance, and they lied about us to the press.

Interest groups have also sought to curb Palestinian solidarity by cynically redefining anti-Zionism as inherently antisemitic. The working definition of antisemitism advocated by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is highly controversial, even among pro-Israel and Jewish bodies, on account of its vague scope. Seven of its eleven illustrative examples of antisemitism relate to criticising Israel. These include ‘claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor’ and comparing ‘Israeli policy to that of the Nazis’. Advocated by various pro-Israel lobby groups and think tanks, IHRA’s definition has gained expanding institutional recognition, inserting itself into governance of the tertiary sector in direct response to campus protests. In Australia, the ‘Group of Eight’ endorsed a definition that views ‘calls for the elimination of the State of Israel,’ and holding ‘Jewish individuals or communities responsible for Israel’s actions’ as antisemitic, and declares Zionism ‘a core part of… most Jewish Australians… Jewish identity’. The NTEU raised concerns that this could be used to ‘suppress valid research and teaching’ and ‘legitimate scholarly debate about different forms of state organisation in relation to Israel and Palestine’.

When lobby groups, often funded through Israel’s Military-Industrial interests, create and enforce their own definitions of antisemitism, they bypass academics, circumscribe their scope of inquiry, and curtail their intellectual freedom, further diminishing the role and value of academic expertise in favour of capital interests. This Orwellian political strategy extends to its harrowing extreme in Gaza, where Israel has sought to undermine Palestinian self-determination with a concerted assault on Palestinian education. By the middle of 2024, ‘more than 80% of schools in Gaza’ were ‘damaged or destroyed’, including all Gazan Universities. Israel forcibly closed all schools in Gaza and many more in the occupied territories. Israel’s systematic destruction of education institutions and killing of teachers and students amounts to ‘scholasticide’.

While ‘the neoliberal University [functions in] conformity and compliance with acts of militarized violence and political domination’, the contemporary campus has cultivated cultures of resisting ‘colonial, racist violence’ sowed in the post-WWII welfare-era. Holding an inadvertent black mirror to the ‘tent city’ protest staged in 1992 against cuts to affordable student housing, I remember someone at camp once joking that they ‘could finally afford to live on campus’, in a nod to the exorbitant and ever-increasing cost of rent at residential colleges. Despite frequent acknowledgement of our relative privilege in the global economic order, the intensifying stratification of tertiary education helps build the political consciousness of the minority and working-class and student activists who collectivised through the Encampment.

The Encampment enacted an ‘alternative to the corporate University’ campus—a critical, reflexive place for teaching, learning and action, against and outside neoliberal institutionalism. Teach-ins were held in frosty dusk light beyond the rhythms of the business day, while hot meals were shared in conditions more familial than transactional. Participants read and discussed theory and strategy, politics and history, faith and despair, moving at a deliberated pace reserved for matters too urgent to rush. Even amid deadlines, conflicts, and the ever-present spectre of individualism, we shared in reflection, solidarity, grief and determination in ways that defied the input and output measures governing our workplaces and classrooms beyond.

The Encampment became a necessary place for sustaining our collective humanity through a refusal to turn away from the Palestinian people’s struggle. Yet, devastatingly, this was not enough. In July of 2024, during the Encampment itself, ANU launched its Defence Institute and Defence Reference Group, explicitly tasked with ‘fostering collaboration and partnerships between ANU, the Defence sector and industry leaders’. That same year, the university also introduced a major and minor in ‘nuclear systems’ to support ‘the AUKUS trilateral security partnership’, even hosting ‘a two-day symposium’. The university’s hostility lay in the fact that meeting our simple demands would require abandoning their key fiscal strategy. It would mean admitting that the institution’s survival is contingent on the continuation and expansion of warmongering. The weight of powerful economic incentives was never on our side. However, each action reshapes the discourse and develops our skills and resources to continue resisting. The encampments, as others have observed, ‘helped to revive and strengthen a politics of left internationalism during a period of world-systemic declines in left politics’. Recent worldwide solidarity marches and the internationalist Sumut Flotilla stand as evidence of the shifting discourse to which we contributed. Increasingly, people recognise the corruption and violence that is endemic to the current political-economic order. We are rising against it.

The expanding MIAC, enabled by neoliberalisation, corrodes academic institutions by manufacturing consent to embedding our political economy ever deeper within violent imperialism. Over the last half-century, ANU students and staff have witnessed the growth of the MIAC and resisted many of its incursions, expanding our political toolkit and sharpening our consciousnesses. This symbiosis between military, industrial and academic sectors places University students and staff ‘in a position of significant structural power’ to confront imperial violence. At present, our political economies are structured by the logics of profit, the forces of accumulation, and the racist violence of colonialism and imperialism. However, like our US comrades, we insist that humanity, in every sense of the word, must determine our collective future:

‘Our fight, parallel to the Palestinian fight, will not be Palestine’s liberation in and of itself. … The people of Palestine will be the ones to ultimately break down the apartheid walls …Our fight is at the university…our insistence on a liberated campus, in every aspect, is inextricable from the call to liberate Palestine.’

- (Columbia Students Grace Wilson and Hannah Smith 2024, 63).

Al Jazeera. 2024. “How Israel Has Destroyed Gaza’s Schools and Universities.” Israel-Palestine Conflict News. Al Jazeera Andd News Agencies, January 24. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/24/how-israel-has-destroyed-gazas-scho ols-and-universities.

ANU. 2022. “Student Activism at the ANU.” ANU Turns 75, July 29. https://anu75.anu.edu.au/protest-student-activism-anu.

Australian National University. 2024. Annual Report 2024. Canberra.

Bell, Geneveive. 2025. Vice Chancellors Statement: Annual Report 2024. Australian National University. https://www.anu.edu.au/about/strategic-planning/annual-report-2024.

Cerami, Carola. 2025. “A Reflection on Global Protests over Gaza: The Role of Universities in the Public Debate.” NAD - Nuovi Autoritarismi e Democrazie: Diritto, Istituzioni e Società, Vol.6, N.2, ahead of print, January 6. https://doi.org/10.54103/2612-6672/27754.

Chowdhury, Raida. 2024. “Emails Accessed by Woroni Reveal Encampment’s Multiple Attempts to Negotiate with the ANU.” Woroni, May 31. https://www.woroni.com.au/news/emails-accessed-by-woroni-reveals-encampments-multiple-attempts-to-negotiate-with-the-anu/.

Connell, Raewyn. 2015. “Australian Universities Under Neoliberal Management: The Deepening Crisis.” International Higher Education, no. 81 (May): 23–25. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2015.81.8740.

Crawford, Charlie. 2024. “ANU Orders Students to Vacate the Encampment.” Woroni, May 27. https://www.woroni.com.au/news/anu-orders-students-to-vacate-the-encampment/.

Dolan-Evans, Elliot, and Giles Fielke. 2024. “These Ignorant Students and Their Emancipatory Politics: What Universities Can Learn from the Protests against the War in Gaza.” ABC Religion & Ethics, May 20. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/australian-universities-can-learn-from-students protest-war-gaza/103867322.

Duffy, Conor. 2025. “New Definition of Antisemitism Endorsed by 39 Universities.” ABC News, February 25. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-02-26/universities-to-enforce-joint-antisemiti sm-position-on-campuses/104980836.

Editors, The Woroni. 2023. “Support Your Teachers, Support the Strikes.” Woroni, July 24. https://www.woroni.com.au/words/editorial-support-your-teachers-support-the-st rikes/.

Foran, Clare. 2024. “House Passes Antisemitism Bill as Johnson Highlights Campus Protests.” CNN Politics. CNN, May 1. https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/01/politics/house-vote-antisemitism-awareness-a ct.

Gülsüm Acar, Yasemin, Ana Figueiredo, Maja Kutlaca, et al. 2024. “Why Protest When It Is Not Working? The Complexities of Efficacy in the Current Palestine Solidarity Protests.” Social Psychological Review 26 (1): 10–17. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsspr.2024.26.1.10.

Honi Soit editors. 2024. “Seeds of Solidarity in the Ground: At the University of Sydney Gaza Solidarity Encampment.” Overland Literary Journal, May 9. https://overland.org.au/2024/05/seeds-of-solidarity-in-the-ground-at-the-univers ity-of-sydney-gaza-solidarity-encampment/.

Internation Holocaust Remembrance Association. 2016. “What Is Antisemitism?” May 26. https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definition-antisemitism.

Ittimani, Luca. 2023. “Protest Won’t Scrap AUKUS – but It Could Undermine It.” Woroni, August 30. https://www.woroni.com.au/news/analysis-protest-wont-scrap-aukus-but-it-could -undermine-it/.

Kacker, Madhav. 2024. “ANU’s Military Partnerships.” Woroni, May 16. https://www.woroni.com.au/news/anus-military-partnerships/.

Kampark, Binoy. 2024. “Students Push for Divestment from Military-Industrial Complex.” Politics: Opinion. Independent Australia, May 1. https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/students-push-for-divest ment-from-military-industrial-complex,18562.

Kortam, Marie. 2025. “The Student Movement for Justice in Gaza.” In Young People in Times of Crises: Global Revelations and Social Change, edited by Susan Eriksson and Alexis Buettgen. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Lindsay, Bruce. 2015. “Markets, Discipline, Students: Governing Student Conduct and Performance in the University.” In Through A Glass Darkly, edited by Margaret Thornton. The Social Sciences Look at the Neoliberal University. ANU Press. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org.virtual.anu.edu.au/stable/j.ctt13wwvss.15.

Marcus, Caroline. 2024. “PM Doubles down on Condemnation of Anti-Israel Slogan | Sky News Australia.” Sky News Australia, May 7. https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/politics/anthony-albanese-issues-str ongest-condemnation-yet-of-antiisrael-slogan-from-the-river-to-the-sea-in-intervie w-for-josh-frydenbergs-new-documentary/news-story/4cc00e220ad78e67bc1cc418 1e2f0250.

Mueller, Jason C. n.d. “A New Political Diagonal: How Students in the United States Constructed Internationalist Solidarity with Palestine.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 0 (0): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2025.2523824.

National Tertiary Education Union. 2025. “NTEU Statement on Universities Australia Definition of Antisemitism.” March 11. https://www.nteu.au/News_Articles/National/NTEU_statement_on_Universities _Australia_definition_of%20antisemitism.aspx.

OHCHR. 2024. “UN Experts Deeply Concerned over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza.” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, April 18. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/04/un-experts-deeply-concerned over-scholasticide-gaza.

Palmer, Nigel. 2015. “The Modern University and Its Transaction with Students.” In Through A Glass Darkly, edited by Margaret Thornton. The Social Sciences Look at the Neoliberal University. ANU Press. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org.virtual.anu.edu.au/stable/j.ctt13wwvss.14.

Penslar, Derek. 2022. “Who’s Afraid of Defining Antisemitism?” Antisemitism Studies 6 (1): 133–45.

Shafik, Minouche. 2024. “Statement from Columbia University President Minouche Shafik.” April 19. Columbia University: Office of the President. https://president.columbia.edu/news/statement-columbia-university-president-mi nouche-shafik-4-29.

Thornton, Margaret. 2015. “Introduction: The Retreat from the Critical.” In Through A Glass Darkly, edited by Margaret Thornton. The Social Sciences Look at the Neoliberal University. ANU Press. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org.virtual.anu.edu.au/stable/j.ctt13wwvss.6.

Troath, Sian. 2023. “The Political Economy of Australian Militarism: On the Emergent Military–Industrial–Academic Complex.” Journal of Global Security Studies 8 (4): ogad018. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogad018.

United Nations. 2025. “UNRWA Continues Its Work in Gaza despite a Ban and the Destruction of the Education System.” United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe, September 3. https://unric.org/en/unrwa-continues-its-work-in-gaza-despite-a-ban-and-the-des truction-of-the-education-system/.

Wilson, Grace, and Hannah Smith. 2024. “The Temporal Politics of Protest: Multidimensionality and Utopia in the Gaza Solidarity Encampment.” Diacritics 52 (1): 50–66.

Woroni Editor. 2024. “ANU Cuts off Power from Encampment.” Woroni, July 26. https://www.woroni.com.au/news/anu-cuts-off-power-from-encampment/.

Yohanan, Nurit. 2025. “Israel Shutters UNRWA Schools in East Jerusalem, in Line with Ban on Aid Agency.” The Times of Israel, May 8. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-shutters-unrwa-schools-in-east-jerusalem-in -line-with-ban-on-aid-agency/.